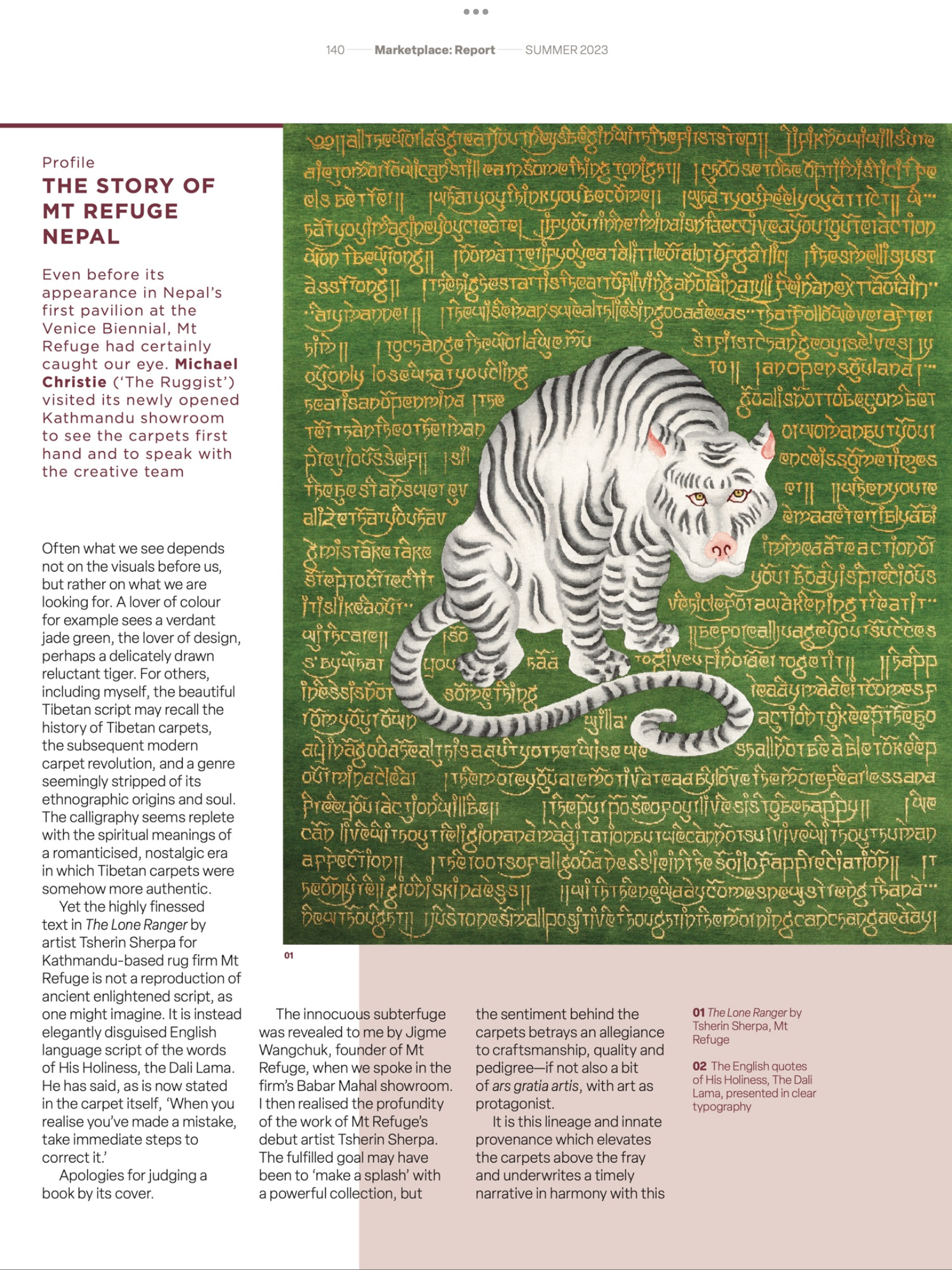

This article came to be quite serendipitously in March 2023 while I was already in Kathmandu, Nepal for field work related to Establishing Trade for a firm in that great city. Having learnt previously of the work of Mt. Refuge, I took it upon myself to see the carpets firsthand at the then recently opened showroom of the firm, which then lead to this Summer 2023 article in COVER Magazine. Presented first is the article as it appears in COVER, whereas second is the original text; it should be noted that I approved the edited version – space is always an issue in print – and have offered the original as a ‘writer’s cut’ if you will, with more theatrical flourishes and embellishment. Enjoy!

The Story of Mt. Refuge Nepal

Article as it appeared in COVER.

Even before its appearance in Nepal’s first pavilion at the Venice Biennial, Mt Refuge had certainly caught our eve. Michael Christie (‘The Ruggist’) visited its newly opened Kathmandu showroom to see the carpets first hand and to speak with the creative team.

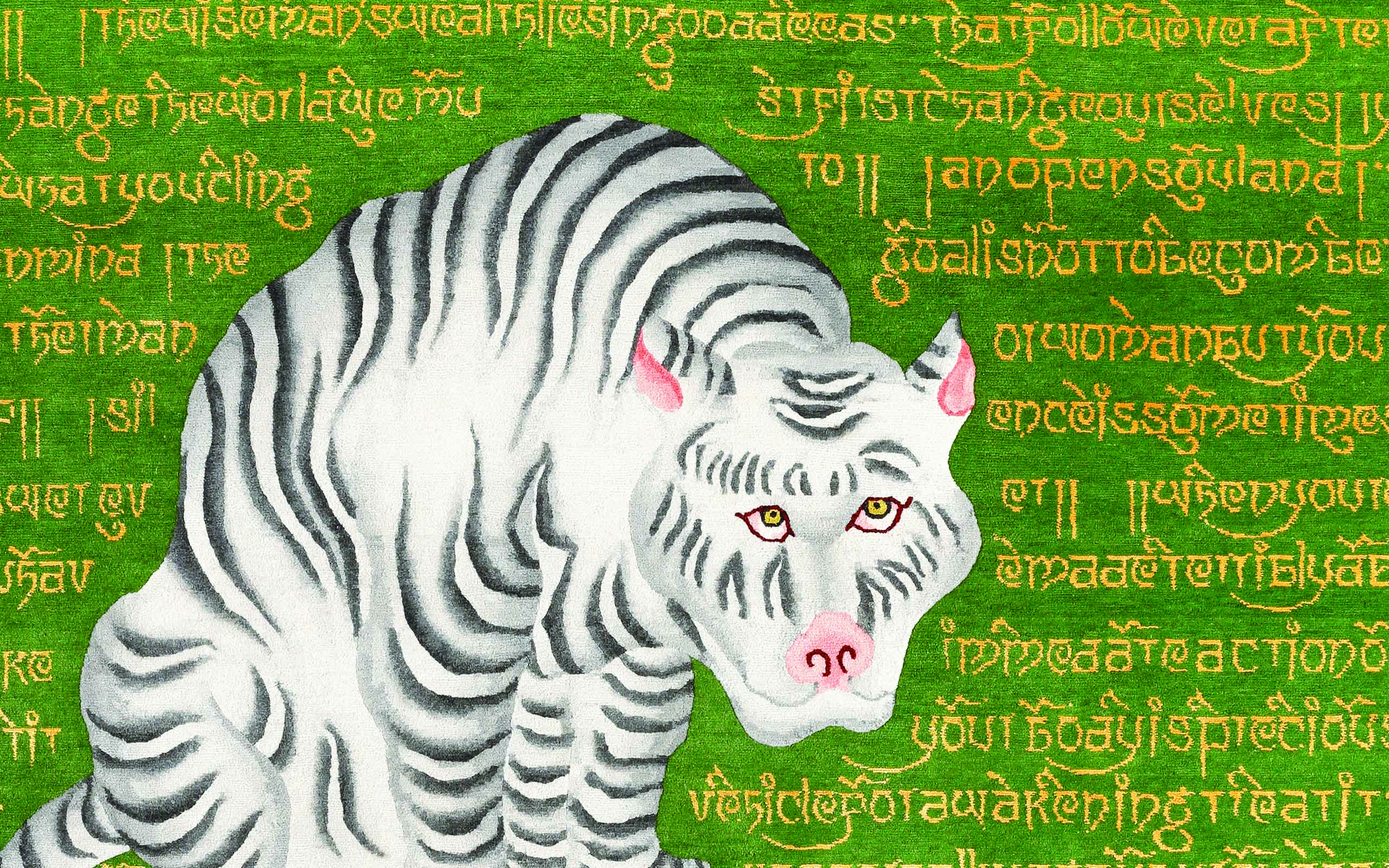

Often what we see depends not on the visuals before us, but rather on what we are looking for. A lover of colour for example sees a verdant jade green, the lover of design, perhaps a delicately drawn reluctant tiger. For others, including myself, the beautiful Tibetan script may recall the history of Tibetan carpets, the subsequent modern carpet revolution, and a genre seemingly stripped of its ethnographic origins and soul. The calligraphy seems replete with the spiritual meanings of a romanticised, nostalgic era in which Tibetan carpets were somehow more authentic.

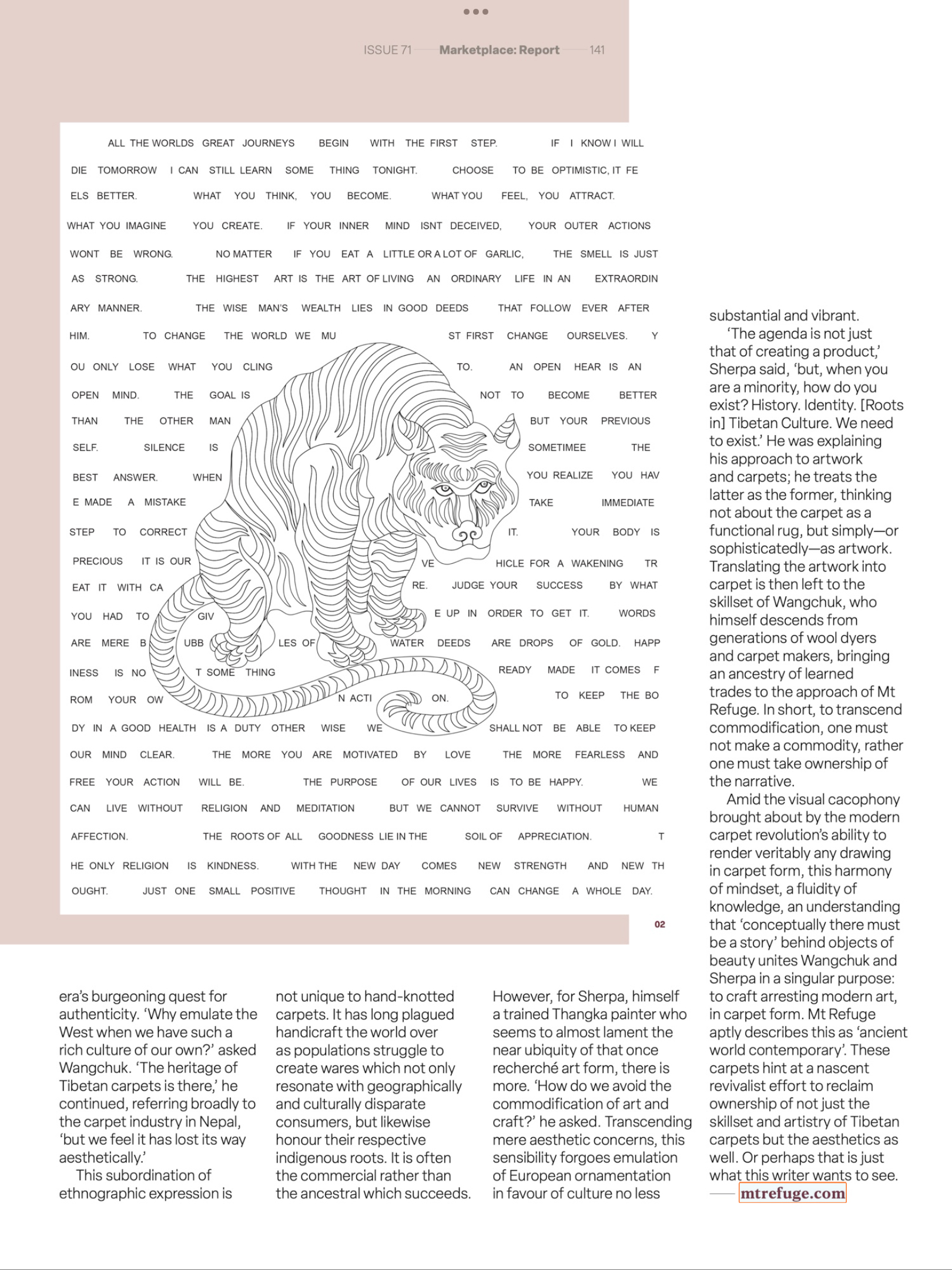

Yet the highly finessed text in The Lone Ranger by artist Tsherin Sherpa for Kathmandu-based rug firm Mt. Refuge is not a reproduction of ancient enlightened script, as one might imagine. It is instead elegantly disguised English language script of the words of His Holiness, the Dali Lama. He has said, as is now stated in the carpet itself, ‘When you realise you’ve made a mistake, take immediate steps to correct it.

Apologies for judging a book by its cover.

The innocuous subterfuge was revealed to me by Jigme Wangchuk, founder of Mt. Refuge, when we spoke in the firm’s Babar Mahal showroom. I then realised the profundity of the work of Mt Refuge’s debut artist Tsherin Sherpa. The fulfilled goal may have been to ‘make a splash’ with a powerful collection, but the sentiment behind the carpets betrays an allegiance to craftsmanship, quality and pedigree – if not also a bit of ars gratia artis, with art as protagonist.

It is this lineage and innate provenance which elevates the carpets above the fray and underwrites a timely narrative in harmony with this era’s burgeoning quest for authenticity. ‘Why emulate the West when we have such a rich culture of our own?’ asked Wangchuk. ‘The heritage of Tibetan carpets is there, he continued, referring broadly to the carpet industry in Nepal, ‘but we feel it has lost its way aesthetically.’

This subordination of ethnographic expression is not unique to hand-knotted carpets. It has long plagued handicraft the world over as populations struggle to create wares which not only resonate with geographically and culturally disparate consumers, but likewise honour their respective indigenous roots. It is often the commercial rather than the ancestral which succeeds.

However, for Sherpa, himself a trained Thangka painter who seems to almost lament the near ubiquity of that once recherché art form, there is more. ‘How do we avoid the commodification of art and craft?’ he asked. Transcending mere aesthetic concerns, this sensibility forgoes emulation of European ornamentation in favour of culture no less substantial and vibrant.

‘The agenda is not just that of creating a product’ Sherpa said, ‘but, when you are a minority, how do you exist? History. Identity. [Roots in] Tibetan Culture. We need to exist.’ He was explaining his approach to artwork and carpets; he treats the latter as the former, thinking not about the carpet as a functional rug, but simply-or sophisticatedly-as artwork. Translating the artwork into carpet is then left to the skillet of Wangchuk, who himself descends from generations of wool dyers and carpet makers, bringing an ancestry of learned trades to the approach of Mt. Refuge. In short, to transcend commodification, one must not make a commodity, rather one must take ownership of the narrative.

Amid the visual cacophony brought about by the modern carpet revolution’s ability to render veritably any drawing in carpet form, this harmony of mindset, a fluidity of knowledge, an understanding that conceptually there must be a story’ behind objects of beauty unites Wangchuk and Sherpa in a singular purpose: to craft arresting modern art, in carpet form. Mt Refuge aptly describes this as ancient world contemporary!. These carpets hint at a nascent revivalist effort to reclaim ownership of not just the skillet and artistry of Tibetan carpets but the aesthetics as well. Or perhaps that is just what this writer wants to see.

Mt. Refuge Déjà Vu

Original draft submitted to COVER.

After an auspiciously timed entry into the world of rugs with ‘The GIANT Ego-lessness 2022’ (COVER 69, page 142) as well as Nepal’s first pavilion at the Venice Biennial, Mt. Refuge has certainly caught our collective eye. Resolute admirer of carpetry Michael Christie, The Ruggist, visited the newly opened Kathmandu, Nepal showroom of Mt. Refuge to see the carpets firsthand and to speak with this creative team at the vanguard.

Often what we do see depends not upon the visuals before us, rather what we are looking for. A lover of colour for example sees a verdant Jade green, the lover of design, perhaps a delicately drawn reluctant tiger. For others – including this erudite aficionado – the beautiful Tibetan script may recall the history of Tibetan carpets, the subsequent modern carpet revolution, and a genre seemingly stripped of its ethnographic origins and soul; the calligraphy replete with spiritual meanings for those who so choose to believe and as artifact of a romanticized nostalgic era in which Tibetan carpets were somehow more authentic.

Yet these fleeting glances betray a failure known to any first year art student; one who is taught to draw not what they think they see, but what they actually see. For while the wisdom of the script remains firmly adherent to the notion of enlightenment, its visual expression is a clin d’œil to playful cultural roots, a deceptively clever – if you’ll pardon the pun – pulling of the wool over our eyes.

And so it is revealed that the highly finessed text in ‘The Lone Ranger’ by artist Tsherin Sherpa for Kathmandu based rug firm Mt. Refuge is not a reproduction of ancient enlightened script as one might imagine, but is instead elegantly disguised English language script of the words of His Holiness, the Dali Lama who has said, and as is stated in the carpet itself, ‘When you realize you’ve made a mistake, take immediate steps to correct it.’

Apologies for judging a book by its cover.

The innocuous subterfuge thus revealed, as it was to me by Jigme Wangchuk, founder of Mt. Refuge when we spoke in the firm’s Babar Mahal showroom, I realized the profundity of the work of Mt. Refuge’s debut artist Tsherin Sherpa. The fulfilled goal may have been to ‘make a splash’ with a powerful collection, but the sentiment behind the carpets betrays an allegiance to craftsmanship, quality, and pedigree; if not also a bit of ars gratia artis with art as protagonist.

It is this lineage and innate provenance which elevates the carpets above the fray and underwrites a timely narrative in harmony with this era’s burgeoning quest for authenticity. ‘Why emulate the West when we have have such a rich culture of our own?,’ asked Wangchuk as if to prompt a response before he continued, ’The heritage of Tibetan carpets is there,’ he said, referring broadly to the carpet industry in Nepal, but concluded ‘we feel it has lost its way aesthetically.’

This subordination of ethnographic expression is not unique to handknotted carpets, having long plagued handicraft the world over as populations struggle to create wares which not only resonate with geographically and culturally disparate consumers, but likewise honour their respective indigenous roots; and while it is often the commercial rather than the ancestral which succeeds, for Sherpa, himself a trained Thangka painter who seems to almost lament the now near ubiquity of that once recherché art form, there is more. ‘How do we avoid the commodification of art and craft?,’ he asked. Transcending mere aesthetic concerns, this sensibility reveals a leitmotif of ownership which foregoes emulation of European ornamentation in favour of culture no less substantial and vibrant.

‘The agenda is not just that of creating a product,’ but rather ’when you are a minority, how do you exist? History. Identity. [Roots in] Tibetan Culture. We need to exist.’ Sherpa extolled as he explained his approach to artwork and carpets; he treats the latter as the former thinking not about the carpet as a functional rug, rather simply – or sophisticatedly as the case may be – as artwork. Translating the artwork into carpet is then left to the skillset of Wangchuk, who himself descends from generations of wool dyers and carpet makers, bringing an ancestry of learned trades to the approach of Mt. Refuge. In short, to transcend commodification, one must not make a commodity, rather one must take ownership of the narrative.

It is this depth of savoir-faire and expression of overtly Tibetan, albeit decidedly modern, iconography that is as appealing as it is important. Amidst the visual cacophony brought about by the modern carpet revolution’s ability to render veritably any drawing in carpet form, this harmony of mindset, a fluidity of knowledge, an understanding that ‘conceptually there must be a story’ behind objects of beauty unites Wangchuk and Sherpa in a singular purpose: to craft arresting modern art – in carpet form.

But as ‘The Lone Ranger’ also reminds, ‘The roots of all goodness lie in the soil of appreciation,’ so for those who admire and appreciate handknotted carpets as more than just expeditious embellishment for the floor, these carpets hint at a nascent revivalist effort to reclaim ownership, however one might define, of not only the skillset and artistry of Tibetan carpets but the aesthetics as well; a goodness if you will akin to ’ancient world contemporary’ as Mt. Refuge so aptly describes. Or perhaps that is just what this writer wants to see… .