Entrée

There is an English language idiom of dubious, disputed, and often patently false purported origin which reads as follows, ’A picture is worth a thousand words.’ I say this for even the people’s history of the phrase notes several versions of various degrees of interest and compelling believability. I particularly enjoy how author Fred R. Barnard is credited with using the term to promote the use of images in advertisements, with Barnard saying the phrase was ‘a Chinese proverb.’ He would later correct the record saying he fabricated the fictional Chinese origin so people would believe it. Peculiar it is our ability to attribute credibility based on imperfect information, and the air of the exotic.

Regardless, I think in truth the sentiment of this phrase must predate any usage on record for our ability to not only see but comprehend from sight is not confined by language nor its structural and arbitrary rules. It is a fundamental reminder that a singular image or vista, a work of art perhaps, a household objet d’art, whatever it is upon which we gaze, has the ability to convey more emotion and information than words perhaps ever can.

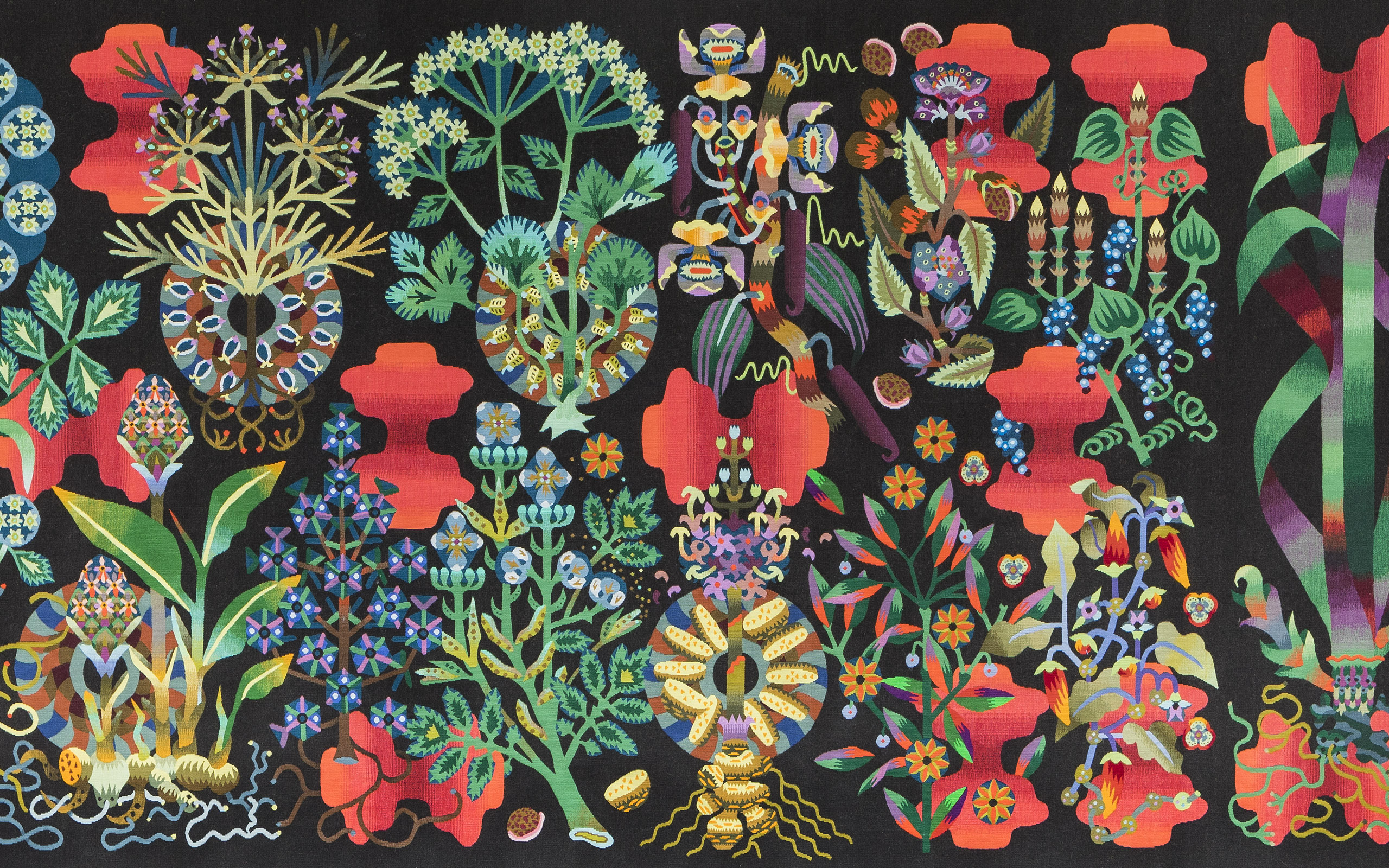

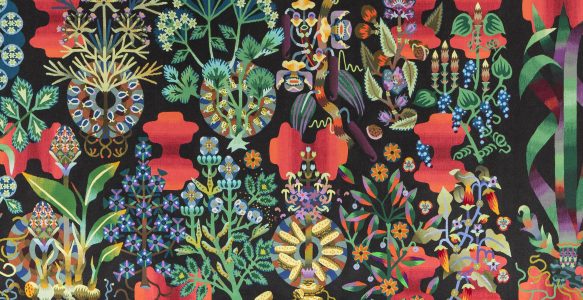

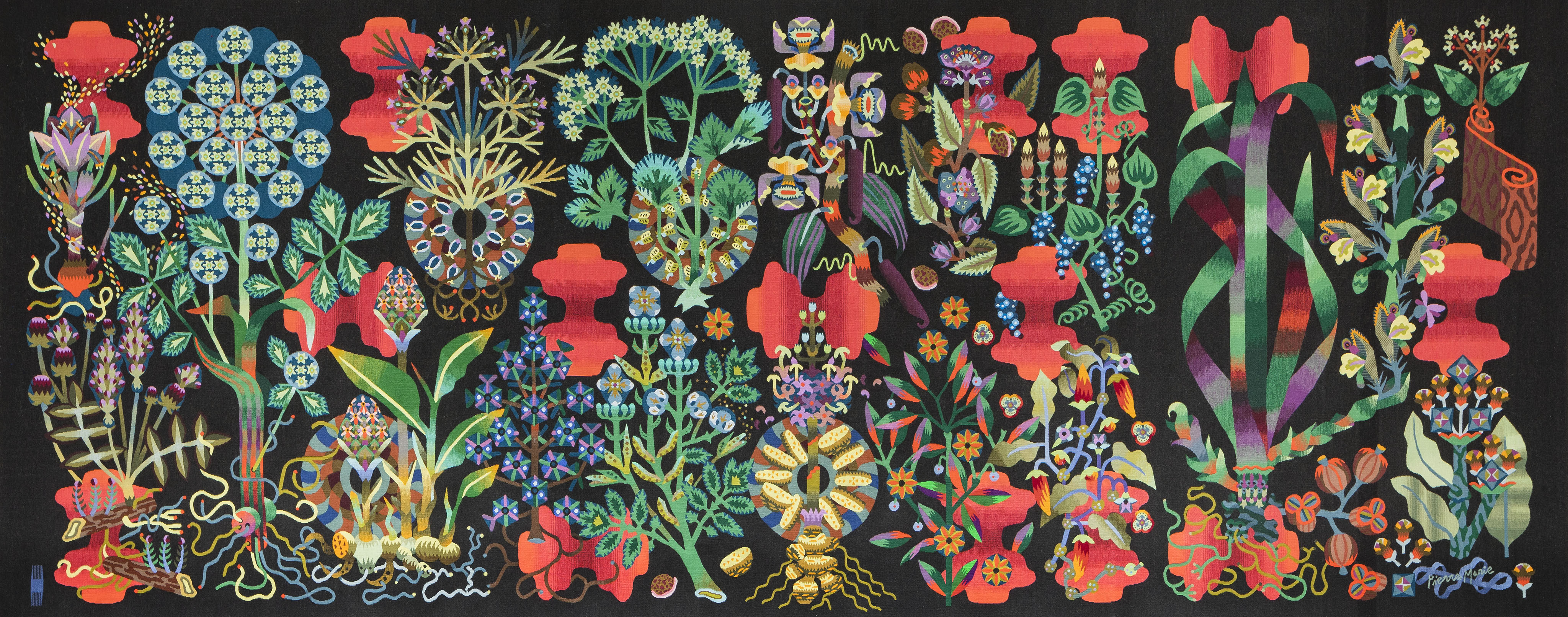

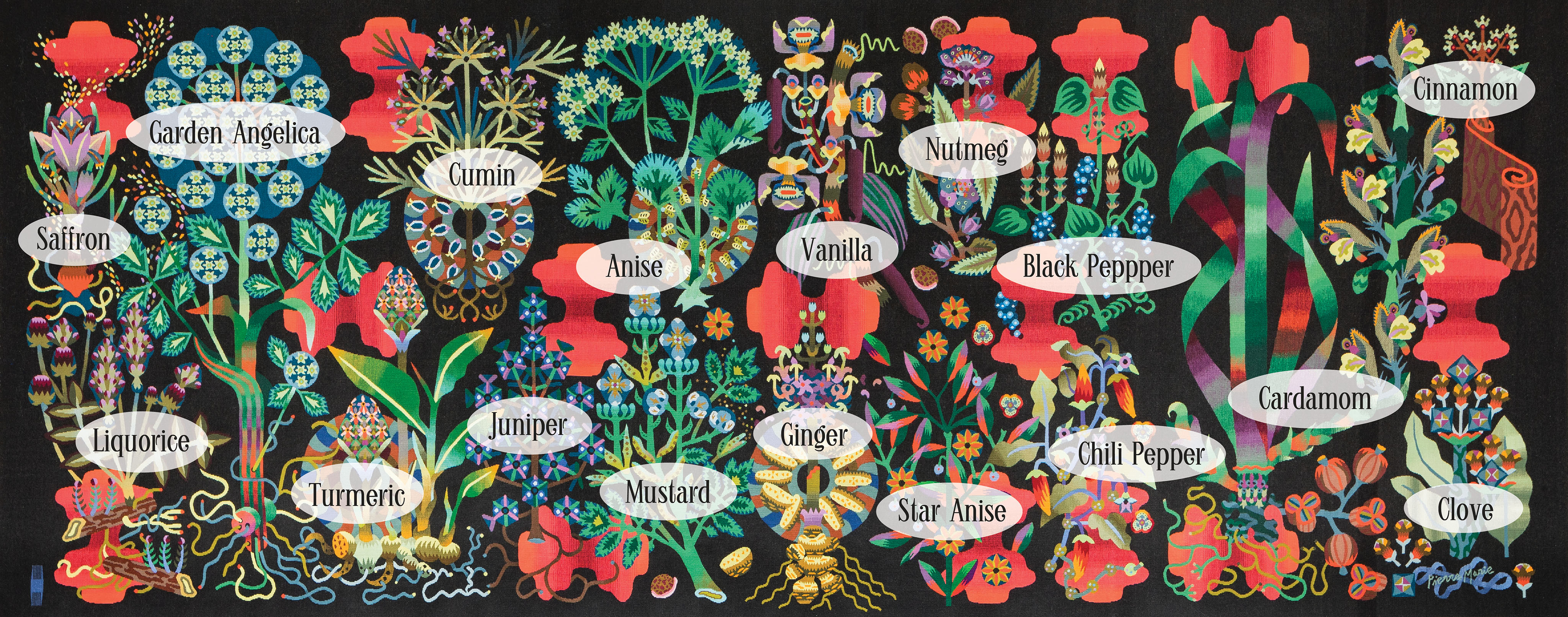

And so begins the telling of the origin of ‘Ras el Hanout’ a magnificent tour de force of technical and artistic achievement in the form of tapestry woven, as it must in this instance be, in Aubusson, France. Designed by Pierre Marie. Fabrique aux Robert Four.

The Story

‘I’ve been fascinated by tapestries since childhood,’ begins Pierre Marie as he replies to interview questions via email, ‘Growing up in a close suburb of Paris, I was lucky enough to visit at an early age the Museum of Cluny in the heart of Paris where ’La Dame à la Licorne’ is hung on display. This early renaissance masterpiece and its ‘mille fiori’ have haunted my mind since then.’

Pierre Marie was born in Nogent-Sur-Marne and as the child of ‘slightly hippie parents’ experienced a happy childhood filled with a passion for Disney animated films and ’an early enduring attraction to colour.’ Now, in 2019, as an accomplished designer in his early late thirties, he has prestigious collaborations with French brands such as Hermes and dyptique within his portfolio, or perhaps more accurately, oeuvre. He sees himself as an ‘artist-ornamentalist,’ that is it say, as Pierre Marie does, he is ‘Someone that has the talent and the knowledge to decorate any surface with a story, a pattern, a frieze. I would just say that some media are more hungry for drawing than others. And textile is definitely one of them.’

As a young artist in his twenties Pierre Marie’s passion for tapestry was further inflamed by the work of Jean Lurçat, Dom Robert and Picart Ledoux; Lurçat a noted artist credited with the revival of contemporary tapestry, the trio all accomplished and embellishing artists who harnessed the potential of tapestry. Pierre Marie, ‘I was extremely moved by their work and I felt very close to their extremely narrative and decorative approach. The naïve yet rich use of patterns, and the strength of their palette were really appealing to me.’

These references and the underlying passion remind this writer of the fictional work ‘The Lady and the Unicorn,’ titled as the English translation of ’La Dame à la Licorne’ – the series of six tapestries which first inspired Pierre Marie. As a work of historical fiction author Tracy Chevalier tells a tale of the making of said tapestries through vivid, if not also slightly passionate – in that harlequinian manner of – storytelling. Embellishments, which in this context one must accept, aside the book conveys the scope of what would have been, and to some degree still is required to make a tapestry propre. I read the book on the recommendation of a rug friend back in 2009 C.E. on a flight, to of all places, Paris.

I mention this as there is a serendipity surrounding ‘Ras el Hanout,’ one difficult to ignore. Galerie Pierre Marie is located in the same arrondissement I stayed in during that trip. The book’s inspiration and passion remind extant artwork, literary, decorative or otherwise, can, shall, and does inspire what is to come. ’La Dame à la Licorne’ as a series represents the various senses and has, woven into its concluding panel, an inscription: ‘À Mon Seul Désir,’ an obscure motto, variously interpretable as ‘to my only/sole desire, ‘according to my desire alone’; ‘by my will alone,’ ‘love desires only beauty of soul,’ ‘to calm passion.’ Regardless as to how one chooses to translate ‘À Mon Seul Désir,’ in many ways the work of Pierre Marie embodies this desire, with seminal works such as ’La Dame à la Licorne’ now joined by modern tapestry no less magnificent albeit reflective of this time instead of arbitrarily conforming to imagery of the past.

Pour la Maison

Pierre Marie did not embark on the making of this tapestry as a grand commercial endeavour, nor as objet d’art to adorn his newly opened gallery, rather it was born of the relatable desire to adorn one’s own home with beauty. ‘At first, before I even had the plan to open my own gallery space, this first tapestry was designed for the dining room of my Parisian apartment,’ said Pierre Marie who continues, ‘I don’t cook a lot but I am obsessed with the idea of spices, aromatic plants, and in general the idea of perfume. So I liked the idea of drawing a tasty and odourant [fragrant or aromatic] tapestry, like a giant herbarium with some of the most used spices used in kitchen. The idea of a herbarium creates a direct link with the tradition of ‘mille fiori’ or Aubusson ‘verdures.”

It was only later that the work would be ‘baptized as ‘Ras el Hanout.”

Un bon croquis vaut mieux qu’un long discours.

Attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte

‘A good sketch is better than a long speech.’

Pierre Marie again, ‘I approached Manufacture Robert Four with this desire to create my first tapestry and to reconnect the precious relationship that links the artist and the weaver. When I first went to Aubusson and when Robert Four opened the doors of their manufactory it really felt like the first page of an exciting novel, or more like a saga! I learnt a lot and the exchange I had there with all of the artisans was way beyond my hopes.’

As an established artist-ornamentalist, Pierre Marie was already familiar with textile. ‘I worked a lot in the fashion industry and had many times the occasion to work on projects that taught me all about printing technique, a lot about weaving, knitting, and embroidery too!,’ said Pierre Marie before adding, ‘I also had the chance to work on handknotted rugs in India.’ The latter, as was the impetus for ‘Ras el Hanout,’ as decoration for his own apartment. This segue from artist-ornamentalist to interior design(er) is not abrupt nor perhaps unexpected, rather it harkens to more halcyon, perhaps the pinnacle days of previous gilded ages, during which the role of interior designer was not yet fully categorized by society and design was all encompassing, not just selecting the colour of the sofa, or worse yet, faux art to match said sofa. Rather, this is design more or less unrestrained, the only less being the technical constraints of the medium, something the artist-ornamentalist adapted quickly to.

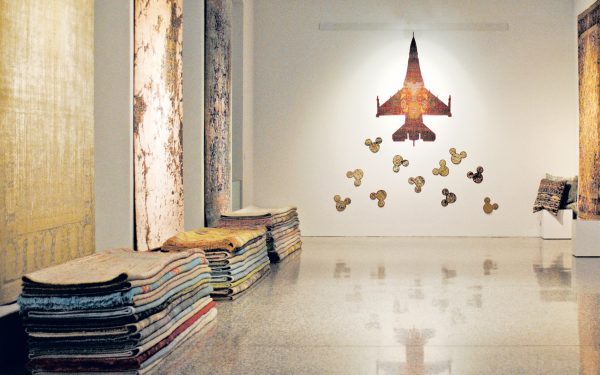

From Pierre Marie’s website describing not only his new gallery space which opened in September 2018 C.E., but also its raison d’etre, ‘Pierre Marie is exploring a new playing field: interior design, which he has chosen to tackle while remaining loyal to patterns and drawing in the spirit of an ‘interior decorator-architect’ similar to the approach taken by the profession in the 19th century. In that era, the decorator took on the tasks of architect, interior decorator, and industrial designer, with a comprehensive approach to interiors that went as far as designing every object and piece of furniture in the room and having them crafted by renowned artists. It is a complete, [fully encompassing] approach in which design comes to life, expands into space and, before our eyes, transitions from [drawing to reality].’

Thus while ‘Ras el Hanout’ was born from an innate personal desire to embellish the home of its designer, it now, especially when shown in situ within Galerie Pierre Marie, offers a glimpse into what an interior designed by Pierre Marie – and all its accoutrements of better living – would look like. In a word: resplendent!

Savoir Faire

Attributing the visual success of ‘Ras el Hanout’ the tapestry solely to the creativity and cumulative multi-faceted experience of Pierre Marie however unjustly minimizes the collaborative nature of craft and it is something the artist-ornamentalist cum interior decorator-architect is acutely aware of. In fact, much as the flavour of the North African spice mix ‘Ras el Hanout’ transcends its constituent components, so too does the French tapestry transcend the sum of its parts acknowledging the fundamental nature of Pierre Marie’s work as the result of ‘…collaborations with craftspeople and craft production factories, [be it] stained glass, rugs, lighting, furniture, et cetera.’

‘The traditional Aubusson embroidery – also known as ‘flat stitch’ or ‘short stitch’ – is fitted onto a basse-lisse loom with a cartoon template inserted into the cotton or linen warp to guide the weaver(s). Manufacture Robert Four has also preserved La Savonnerie’s knotted-pile carpet technique, and remains the only producer with the skills and ability to weave specially commissioned items. Continuing the proud female tradition of this profession, craftswomen known as velouteuses teach and train a new generation of workers at the manufactory, each anticipating the moment of the tombée de métier which could reveal a carpet, a tapestry or a woven furniture covering – who knows which?’

Manufacture Robert Four

His meeting with Sylvie Chazeaux, a weaver in Aubusson, was a revelation. ‘We really have the same sensibilities,’ she explains as quoted by Pierre Marie, ‘For a first woven piece, it is really accomplished, both in terms of the design and the colours and movement depicted. I never tired of weaving it. Each day was full of discoveries. I also reconnected with the pleasure of using weaving techniques employed in the 1930s: dots and stripes. It is truly a piece that was designed for tapestry.’ This design however did not come about as easily as putting pencil to paper, rather is is the result of the artist-ornamentalist learning new techniques, learning to adapt to a new medium in order to excel.

Designed and woven over the course of two (2) years in close collaboration with Manufacture Robert Four in Aubusson, France, the resultant work differs from the original drawings. During the first year Pierre Marie developed the initial drawing and cartoon, which was quite realistic in its interpretation of flora rendered in a naturalistic palette. Unfortunately, or perhaps with great fortune, this approach was rejected once an initial woven sample was produced. Reconciling artistic vision with the realities of Aubusson-stitch tapestry weaving, Pierre Marie realized his drawing was too finely detailed, possessing finesse and curvilinear elements which were not matched with medium. ‘That’s when I understood that I shouldn’t hesitate to mix very raw, bright tones. Avoid excessive overlapping, exaggerate the branches. And to boldly aim for more naïveté, to depict each plant as a logo, resulting in a sort of alphabet,’ summarizes Pierre Marie, who continues.

‘I often say that when I compose an image it feels like I am a hunter setting traps for the eye, traps for the mind; knowing how to captivate one and how to satisfy the other. Knowing how one kind of shape, a certain repetition, a particular colour accent, can please our brains or make it want more. With the story of ‘Ras el Hanout,’ every plant represented is a chance for me to set a new trap and the whole composition a way of making the prey fall in all of the traps one after the other.’

‘As I was looking for a name, I then knew it would be the major piece for my inaugural show [at the new gallery],’ recalls Pierre Marie when asked if he cooks and or is familiar with the namesake spice mix. ‘Yes, ‘Ras El Hanout’ is the name of a secret mix of spice [frequently sold in spice shops] in North Africa, [but] it literally means ‘the front of the shop’ because this mix is displayed outside on the street in front of every store.’ This allows a passing pedestrian and potential customer to freely evaluate the mix and deduce therefrom its quality as well to infer the quality of other products in the store. ‘With this new gallery I also felt I was opening a grocery myself, and that this first tapestry would be the first piece people would see and that they would evaluate the quality of my work from it, I thought it was just the perfect name!’ concludes Pierre Marie.

A Primer

As brief primer to Aubusson-stitch tapestry weaving, it is worth mentioning that as the weaver, tisseuse en français, or as called using an older form as used by Manufacture Robert Four, lissière ou velouteuses, completes row after row of weaving, the tapestry is rolled around a large round beam on the loom. Consequently, once the completed sections are rolled, the full visage of the tapestry is concealed awaiting a dramatic reveal. ‘I went a few times to Aubusson in order to check on the weaving and Manufacture Robert Four would [also] send me pictures, but there was nothing that could prepare me to the shock I had during the big reveal,’ said Pierre Marie who added, ‘It was so emotional. Everybody was crying!’

Further primer on the technique also reveals a ceremonial moment steeped in tradition: tombée de métier, the ‘falling from the loom,’ when the tapestry is removed, via cutting of the warp yarns, from the loom. It’s an irreversible step that concludes the weaving and if one is to believe the narrative told in ‘The Lady and the Unicorn’ it is also the moment when weaver, artist, perhaps even patron, must accept the piece as finished and that it is ready to reveal itself to the world. This parallels Pierre Marie’s own thoughts. ‘Of course the cutting off ceremony is often compared to a birth. The Manufacture invited some of the journalists and professionals who have followed my career. It was really nice that people would be there and would be able to share that incredible energy and testify about it.’

The monumental tapestry thus reveals its commanding scale of 150cm x 365cm (59” x 144”) as well as its palette comprised of two-hundred fifty-nine (259) colours rendered in wool and silk. Completed in July 2018 this is high decorative art at its absolute best in so many ways. A traditional craft, in the sense that the techniques have been used for generations in this same place, terroir if you will, unleashed from the verdures, influenced by recent artists, turned into something fresh and new. It is a great synergism – to reüse that word – that references so much of what helps create a vibrant human culture: collaboration, influence, variety, complements, interpretation, to name but a few. It is also captivatingly beautiful which invites one to ponder – at leisure – the relative merits of Art versus Decorative Art; the former often provocative yet uneasy on the eyes, the latter, owing to its potential visual delights elevated – as is Tapiserie Ras el Hanout – beyond furtive glances, inviting a long uplifting, almost spiritual, contemplative gaze.

Conclusion

I do feel ‘trapped’ as Pierre Marie said but I also feel, as Diana Vreeland would approve, ‘that my eye does have to travel.’ From one logo or vignette to another each reveals a whimsical embellishment of the flora. Be it the textured peeled bark of the cinnamon, the fanciful wisps of saffron in the air, turmeric root, cloves, juniper berries or any of the remainder, each drawing of a plant brings to vivid decorative life not only the structure but the essence of the flavour, or aroma thereof. While the tapestry itself may not posses an intoxicating olfactory attraction, a perfume, its visual appeal – replete with ocular entrapment – conveys that essence, double entendre intended, and remains equally as captivating if not also inebriating.

I would just say that some media are more hungry for drawing than others. And textile is definitely one of them.

Pierre Marie

It also exemplifies the reality faced by designers of textiles – rugs and carpets included. As Pierre Marie admitted, the structure and technical ability of tapestry – and indeed any textile medium – is not necessarily suited to the drawing abilities of the designer, or artist-ornamentalist. His original work was ‘quite realistic in its interpretation of flora rendered in a naturalistic palette’ yet did not translate well into woven form. Not all media can render images realistically, and as such one must question whether realism is indeed the best approach to achieve the desired visual results. Furthermore, the weaving of ‘Ras el Hanout’ in Aubusson, France, redoubt of true Aubusson and Savonnerie construction, likely foreshadows the future realities of authentic handwork and weaving the world over; an eventual niche couture existence. After all, the same sentiment of Pierre Marie expressed via ‘his approach, which resembles that of Jean Lurçat in the 1950s,’ also aligns with those of a new generation of young artists determined to modernize this craft and ‘to reintroduce it to our contemporary interiors,’ sounds uncannily familiar to sentiments expressed about handwoven and handknotted rugs and carpets.

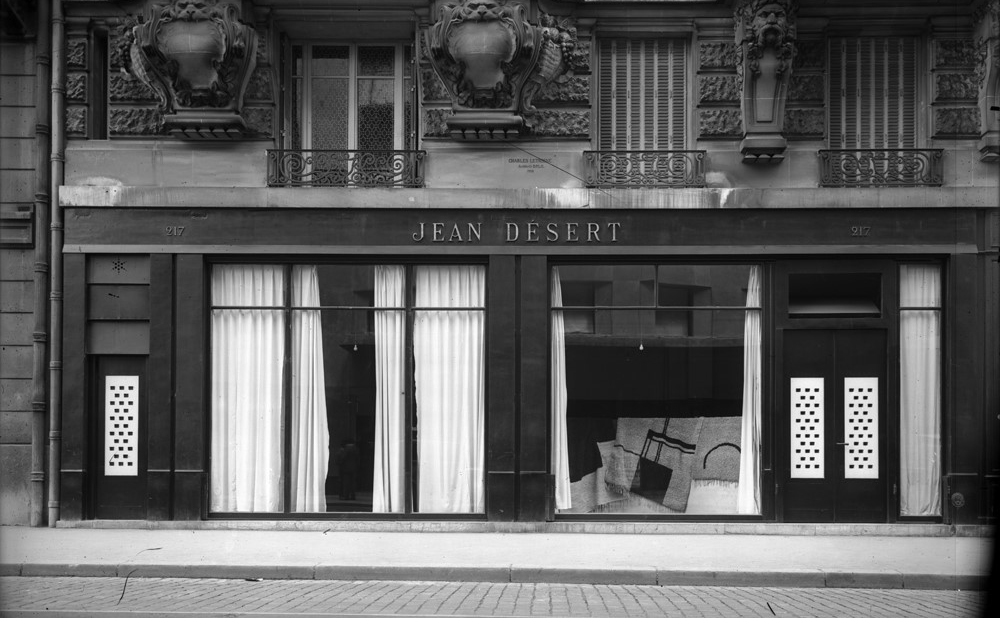

Returning finally to the notion of a picture’s worth in number of words, one must contemplate not only the imagery of ‘Ras el Hanout,’ Galerie Pierre Marie, and the equally as enticing and illustrating Galerie Jean Désert, but also the value, if you will, of any image particularly without context. This can be an elaborate narrative such as this, just as it can be experiencing the haptic and visuals of a textile, be it tapestry, rug, carpet, what have you, with one’s own hands and eyes.

No matter how one experiences a visage, it is unlikely any two (2) interpretations will be identical or, in cases where subjective matters are discussed – even correct. For example, when this writer first saw Tapiserie Ras el Hanout but before researching this article, I convinced myself: 1) That the creator thereof was most assuredly a novice chef; and 2) That this artwork was his secret house formula for a ‘Ras el hanout’ spice blend. Neither of these are true and moreover after comparing the ‘the most used spices used in kitchen’ as collaged by Pierre Marie against this writer cum accomplished-novice-chef’s own house blend, I can attest his formulation is best left to visually delight via the thousand words of the viewers’ imagination as opposed to the taster’s palate.

Perhaps next time then I shall accept the kind offer expressed by Pierre Marie in his closing words to me, ‘I hope this would be the beginning of many other tapestries to come! For the next one I will invite you to the cutting off ceremony. 😀‘

The second show at Galerie Pierre Marie opens on 1 April 2019 C.E. Based on the image which thousand words and what presumably captivating visual delights await… ?