Carpets as Art

Art. Simultaneously heralded, reviled, praised, censored; the list of offences ascribable to art is both verbose and highly subjective much like the genres thereof in sum. Perhaps only surpassable by art critique itself in volume of arbitrarily disputed, discounted, and discarded work, art has the ability to conjure emotions myriad. As provocateur, art is perfectly suited to address directly the issues which have and continue to plague society, including, of course, the issue of art itself. Protected by law to varying degrees, freedom of expression – as art most certainly is – serves as counterbalance to the pendulum swings of liberty, populism, order, chaos, conservatism, neo-liberalism, fascism, the extant and future manifold ‘-isms’ of human interactions, and god, God, or gods know what else. It can also be media largely free of the constraints of written and spoken language, evoking feelings and emotions often difficult to express via written language, though this has yet to stop anyone – this writer included – from trying. This is an attempt do just that; wrap the innumerable interpretations of art – and the convoluted emotions conjured – into a bundle of words.

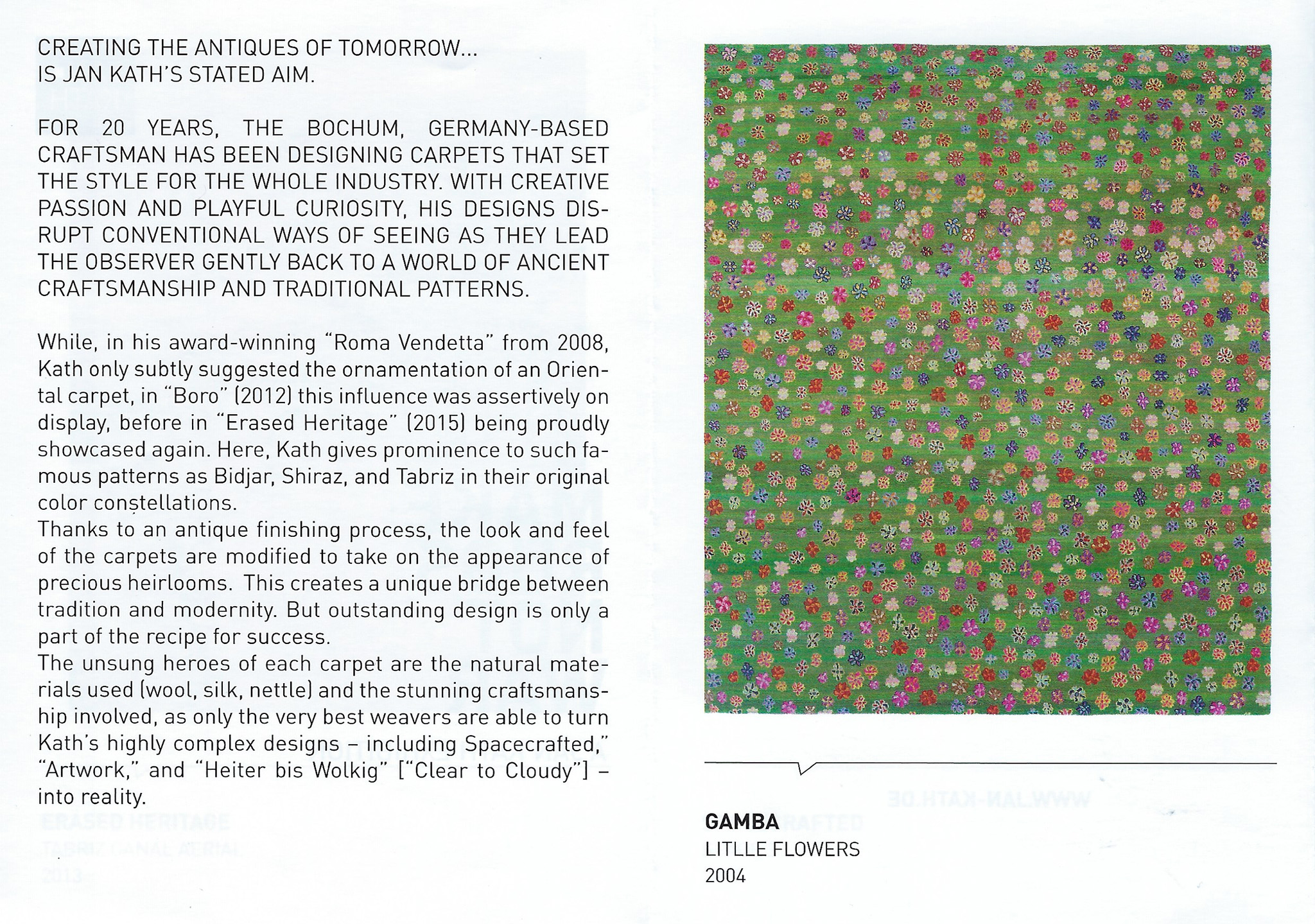

However, it is first necessary to address a commonly repeated and most often incorrect phrase used by those who craft, market, advertise, and sell handmade rugs and carpets: ‘Rugs are art for the floor!’ Perhaps, but scepticism remains. Yes there is artistry in the craft of making a rug – that is, carpetry – but art they are not. To explain… . It all comes down to intent, both on the part of the artist/creator/designer and that of the consumer. If the intent, the purpose of the rug or carpet is to serve as delightful and adorning embellishment to a finished space and/or to complement an interior, if it was selected because of a soothing and agreeable colour palette, if the decision is more decorative than emotional, if it was ordered with fastidious specifications and requirements, if decisions are removed from the maker/designer/weaver in favour of the client, if the rug or carpet does not challenge preëxisting conceptions, then, again, art it is not.

This is most assuredly not to discount the artistry nor talent of those who design or make carpets, rather it is to return nuänce to the discussion, to reclaim language from the distorting minds of those afore alluded marketers. After all, these are people who would have you believe the selection of tchotchkes – no matter how lovely – at Restoration Pottery Pier and Barrel is somehow a curated exhibition of fineries as opposed to a sourced selection of mass produced wares, but I digress.

‘Art cannot be proper. Art must be exaggerated. Art must exaggerate the likeness.’

Stanisław Szukalski

Rug and carpets may well be decorative art for the floor, a distinct and arguably superior subset genre of art which owing to its utility is more akin to craft than fine art, but – broadly speaking – they are not art in the way I believe art should be interpreted in this era. And that reminds, as there was no published artist’s statement nor interpretive verbiage provided, this entire discussion is only my interpretation of Kath’s work and the crude written expression of the emotions stirred by this work, which have been haunting my mind since I first saw the work on 9 January 2019 at Jan Kath in Bochum during ‘A Family Affair’ as well as during the works’ vernissage at Jan Kath Köln by Nyhues on 15 January 2019.

Transcending Decorative Art

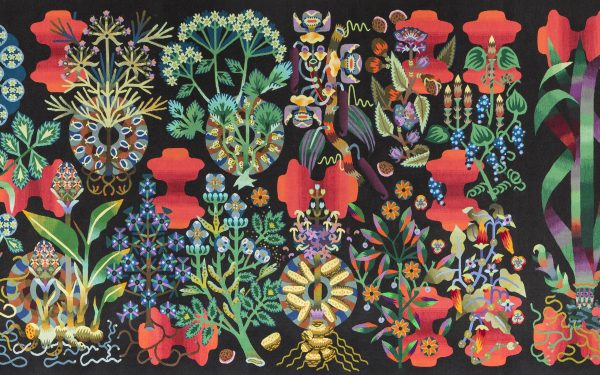

Calling as art the vast majority of rugs and carpets made today is intellectually dishonest and in truth no different than calling mass produced paintings from China that have ‘just the right hint of blue that ties the room together’ art as well. There are of course rare exceptions but in a world driven by design and trends, precious few carpets elevate themselves above the fray into the exalted world of art, or perhaps to best distinguish: Art! This is unquestionably a subjective opinion, one anyone is free to question or challenge, yet to accept broadly rugs and carpets as art is to invite inclusion of many a pastiche object just as it is to delegitimize the work of practicing artists, formally trained, folk, or otherwise. The ensemble of carpets which comprise ‘Make Rugs Not War’ specifically challenge the status quo, and thus, like ‘Pearls’ Passage’ by Viron Erol Vert, transcend decorative art into Art, utilizing the carpet not just as rug, but as medium upon which commentary is imbued.

With that, what is it then that Jan Kath is saying via ‘Make Rugs Not War?’

‘Make Rugs Not War’ is a series of artwork rugs created by the firm Jan Kath which question the status quo of the American Empire be it the policies of the government of the United States of America or the hegemony of American cultural and corporate influence. It is provocative work insomuch that it openly questions power structures of this era, yet the intellectual beauty of these works extend far beyond the scope of the United States, calling into question not only governmental and political policies the world over, but also the actions of Jan Kath as the representative face herein of commerce, of artist, of outsized global influence. For these reasons alone I thoroughly enjoy the work, and let me tell you why; may the discussion provoke thought!

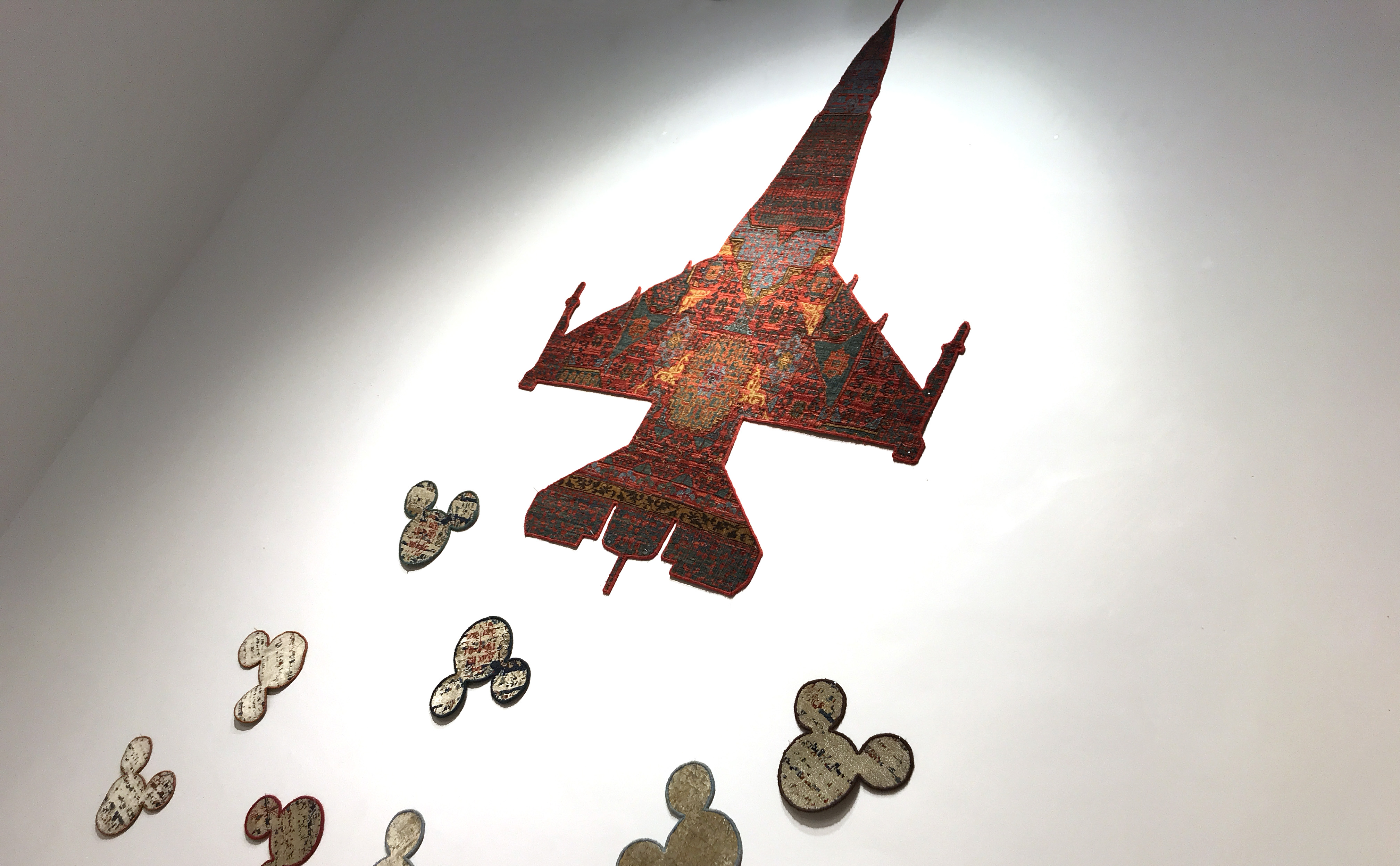

Representative of the Government of the United States and by extension any country within its sphere of influence and/or one which simply has enough ca$h to employ use of the same equipment, the ‘War Plane,’ ‘War Drone,’ and ‘Tank’ (not shown) are legally defended if not sanctioned oppression manifest. Embodying the raining and reigning terror of death which tends to accompany oppression, as well as the corporate cultural hegemony which comes with monopolistic dominance, the ‘Mickey Bombs’ bring capitalistic joy and conformity to the would be magic kingdom of the world. It is brilliant work that must be singled out as such just as it should be springboard from which critique and further questioning arise.

Art must challenge preëxisting conceptions. Art must posses an imbued commentary – implicit, explicit, or otherwise.

Foremost amongst the many rhetorical and literal questions raised by ‘Make Rugs Not War’ is: ‘Why single out the United States?’ This is not asked in defence of the country, for many of the actions of the United States are indeed indefensible, but it is to question the sincerity of criticism itself and moreover who any of us choose to ‘attack,’ to use use the polarizing and hyperbolic language of politics of this era. Much like those of the American Baby Boom Generation who preached the slogan ‘Make Love Not War’ before maturing into the… let’s just say… generation that did not live up to the anti-war slogan, it seems there is potential for the sentiment of ‘Make Rugs Not War’ to not be as grandiose as one might or might not imagine. It is after all an exaggeration of reality, one situated at the uneasy crux of Art, commerce, and politics, and thus it is fitting the interpretations thereof enjoy both an outsized treatment as well as a bit of discomfort.

It is easy to critique those who welcome, embrace, or minimally tolerate dissenting opinions. Canada, the United States, the European Union, even the originators of Orwellian in the United Kingdom all – to varying degrees – protect freedom of expression and so while it is one thing for Kath to critique the actions thereof, it is another to question the might, to speak truth to power, to those who – How is it said in diplomatic language? – are less tolerant of critique. Id est, China, et alia. Likewise, this writer, both long a fanatic of Kath’s work and beneficiary of the firm’s hospitality and grace treads cautiously in the same regard. Idiomatically speaking one might say, don’t bite the hand that feeds you, that is: ‘Do not scorn or treat ill those on whom one depends or derives benefit, for to do so is to risk losing those benefits altogether.’

So it is then in this era, one in which governance and commerce increasingly intertwine, one in which we turn to celebrated social media influencers for advice of value dubious, worthless, factual, exemplary, or otherwise, one in which observable and factual reality itself is questioned, and when post-truth is seen as an acceptable status quo, that we all collectively must in essence ask: Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? Who will guard the guards themselves? Moreover, who will do this in the face of economic uncertainty let alone potentially detrimental personal and social repercussions?

This is the glorious allegory of ‘Make Rugs Not War.’

A Glorious Allegory

Kath questions, and rightly so, the actions of the United States, the military-industrial complex, and so much more, yet he does this in relative safety and comfort. Maybe an American client will see ‘Make Rugs Not War’ and having been so enraged by the sentiment decide to boycott the purchase of a Jan Kath carpet; it is also just as likely that an American client will see ‘Make Rugs Not War’ and buy one, two, or more, rugs from the firm, having a kindred spirit found. In 2019 neither scenario is unreasonable, nor is criticism of the United States and its abhorrent President; every reasonable person can discern the tangible absurdity of the situation and – due to freedoms still enjoyed in the occident – openly question it, if not also call for change.

Of course, this is predicated upon Kath’s work being freely and widely distributed in uncensored form such as it is here yet at the same time, the conspicuous selection of the United States for critique over that of another country begs one to ask: ‘Why?’ If this writer were to speculate, and I am, it has entirely to do with money and power just as this commentary, and veritably everything else does in this day and age. All hail the almighty dollar! While some may see it as uncouth to ask aloud these questions and those that follow, as Jan Kath Design GmbH is predominantly a commercial enterprise – one tacitly if not overtly endorsing ‘Make Rugs Not War’ – it is not unreasonable to question the financial motivations and considerations.

‘The prime goal of censorship is to promote ignorance, whether it is done via lying and bowdlerized school texts or by attacking individual books [or art; any media of expression.]’

Felice Picano

Consider if you will, the implications of a similarly constructed artwork which, instead of depicting an American tank, war plane, or drone, were in its stead to depict a Chinese tank metaphorically shooting tiny Winnie the Poo bears6. This is categorically not whataboutism for every entity – state, company, individual, or otherwise – can always find improvement, rather it is to remind that not all criticism is tolerated and moreover that criticism of the government of the People’s Republic of China – or the authoritarian country of your choosing – carries with it consequences, often grave. Few if any in number are those who openly question or critique Chinese authority and simultaneously enjoy success in the country. Simply put, the rules, if you will, of occidental and oriental societies – to use slightly outmoded terms – can be and are quite different, yet in this era are on a more sinister, repressive, and oddly convergent path than one such as myself might have imagined in our youth.

As an American by birth I was raised to believe in and to defend – with the implied, by any means necessary – freedom of speech. Now called freedom of expression by most defenders thereof, it is a central tenet of democracy and it is one which protects the citizenry from Government sanctioned oppression and censorship. Unfortunately or by design, when commerce and governance become intertwined – such as in China or the authoritarian country of your choosing – and said state is not tolerant of criticism – such as in China or the authoritarian country of your choosing – it is euphemistically ‘challenging’ to be openly critical of the government and still run a successful business.

‘But you can’t make people listen. They have to come round in their own time, wondering what happened and why the world blew up around them. It can’t last.’

Likewise and with acknowledgement the consequences are drastically different in scale, this is the same dilemma faced regularly by those who write about subjects varied, perhaps even rugs and carpets; ‘Make Rugs Not War’ resonates for this very reason. What to write, whom to critique, and countless other questions which may bite at the hand which feeds. At its most primal, it reminds of the struggle to do right in world governed by irrational beings who, even if given perfect information, often make decisions not in their own best interests. C’est la guerre.

‘As a condition for entry into the Chinese market, Apple had to agree to the Chinese government’s censorship criteria in vetting the content of all iPhone apps available for download on devices sold in mainland China.’

Rebecca Mackinnon

‘Make Rugs Not War’ also inherently reminds of the failures of the past, of slogans not backed by sustained action. Whether we make love or rugs – Why (k)not both? Why (k)not love rugs? – instead of war, we must remember paradoxically to always be at figurative war with literal war; this is not a battle that ends, though it should not require a lowly commentator of rugs and carpets to highlight what should be a readily apparent distinction. Societally we have nowhere near perfect information, yet the sum of human experience provides more than ample to reflect upon. Successive generations and cohorts, the people of this era, thus contemplating the immutability of what has been in order to learn and then, ideally, improve upon the extant. It’s the aphorism attributed to George Santayana: ‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.’

‘To hold a pen is to be at war.’

Voltaire

Conclusion

It is then that ‘Make Rugs Not War’ is less a feel good nostalgic ode to a hippy dippy era than it is reminder of civilization’s failures. It recalls oppression and censorship. It symbolizes the potentially chimeric, nefarious, and malignant nature of commerce and government intertwined with common goals – no matter the cause. The charmingly delightful and seemingly innocuous ‘Mickey Bombs’ – as stand in for any relatively large scale enterprise – morbidly disguise the diversity eroding nature of consolidation, market dominance, and corporate greed, as well as the pacifying nature of panem et circenses enacted not directly by the state, but by proxy. At the extreme ‘Make Rugs Not War’ hints of the corrosive nature of censorship through ‘creative omission.’

‘Self-censorship is a lie to yourself; if you are going to be trying to seriously create art, to create literary art, and you decide to hold back, to censor yourself, then you are a fool to yourself and it would be better that you kept your mouth shut and did not speak.’ – Salman Rushdie

It is with the utmost of respect I authored this commentary on ‘Make Rugs Not War’ for Jan Kath does, in this instance, great service fostering the dialog a healthy society so requires. We must all be open to criticism, to critique, to grading, just as we all must daily make decisions regarding who to criticize, critique, and judge. Kath chose the United States, a relatively safe object in my opinion, yet to choose China – or the authoritarian country of your choosing – is to invite more than one might care to deal with, the feeding hand thusly withdrawn. This vexatious quandary plagues not only Kath and this writer, but anyone who values a free and open society. Uncomfortable as some discussions may be, they must be had.

In the highly subjective world of art and art criticism (another of humanity’s ‘-isms’) and the blurred lines illustrated herein between Art! (as valid commentary on society), art (as reasonably accurate descriptor for many an artful commercial ware), and art (as marketer’s dubious adjective to entice you to part with money), ‘Make Rugs Not War’ provides ample inspiration for productive thought. The world desperately needs more commentary such as that of Kath’s just as it requires opinion – concurrent, dissenting, or otherwise – across all society. However caution must be heeded lest we relinquish the role of critic to commercial concerns which likely do not align with those of society en masse.

Go forth and ‘Make Rugs Not War,’ whatever that may mean to you.

[Editors note: The article was published on 14 April 2019. At the recommendation of a valued friend and colleague, the penultimate paragraph, the interjection ‘…as there was no published artist’s statement nor interpretive verbiage provided… ,’ as well as the scan of the inside of the pamphlet were added on 18 April 2019 to further clarify and add nuänce to the discussion.]