This article was originally written for the 2022 Annual Publication of the Nepal Carpet Manufacturers and Exporters Association (NCMEA). It appears here with their endorsement as to broaden the audience. Without coöperation and reïnvention in this regard it is this author’s fear that carpetry in Nepal will continue to decline.1

The production of carpets in Kathmandu has had a transformative effect on both the Tibetan refugee population and the native Nepali people. It is an industry which during its ascent, golden years, and decline – in volume – provided much needed foreign exchange for a country dependent upon such transactions. It created wealth both in Nepal and abroad, and it has undoubtably contributed to an increased standard of living in the country of Nepal. Likewise, carpetry in Nepal has transcended its ethnographic origins in Tibetan culture and traditions, merging harmoniously with the people of Nepal, and the demands of Western consumers upon which the commercialized trade of today depends. Despite well-intentioned, if not also self-serving claims of lost authenticity as Tibetan carpetry evolved, carpets produced today are indeed the progeny of a long and storied tradition.

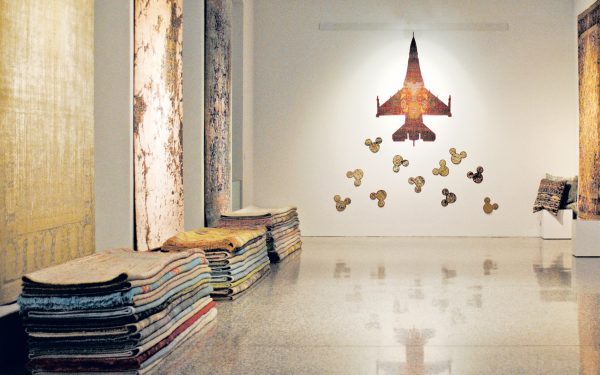

Any maker in any place can make a cheap knock-off version of a Nepali-Tibetan carpet. Only Nepal can make what is now, genealogically speaking, the true Tibetan carpet. This is no different than it has been since rug making in Nepal was commercialized, but this distinction must now be exploited by the makers and exporters of Nepal. But how?

From its nascent beginnings in the 1980s through to today carpet weaving has matured, developing a finesse and fidelity which is envied, celebrated, and mimicked – though not duplicated – throughout the rug making and consumer world. It is now truly Nepali-Tibetan owing to the generations of both cultures which have created a truly world class – and unique – production environment.

It is likewise an industry requiring rebirth. Not because what was built and what exists is failed, but rather because the conditions upon which the success of the past were built simply no longer exist. As Dr. Tom O’Neill writes in his circa March 1999 paper ‘The Lives of the Tibeto-Nepalese Carpet,’ ‘What made this sudden and spectacular growth possible was a combination of steady product development by German buyers and Tibetan refugee or Nepalese owners, and the coincidental popularity of Tibeto-Nepalese carpets in Europe. Tibetan carpets were no longer only luxury goods displayed by connoisseurs; they became available at inexpensive prices to consumers not as concerned with authenticity as with physical and aesthetic qualities.’2

Pioneered and promoted as a means to provide for refugees, the success truly hinged upon two points Dr. O’Neill highlights: coincidental popularity and inexpensive prices to consumers. These conditions – amongst several others – no longer exist, others however remain the same. For example, in the same paper, Dr. O’Neill writes of weaver shortages in the early post-refugee production period; a problem which still irritates production in Kathmandu.

While it would be foolish to discard what exists today, makers and manufacturers in Nepal, Kathmandu specifically, must consider changing their business models if they are to adapt to the demands of today. As my dear friends in Nepal are apt to say, ‘We do hope conditions and sales will improve,’ but as wise individuals we should make plans which foster future success by incorporating all we know about tradition, the needs of today, and the anticipated needs of tomorrow.

The ‘coincidental popularity’ of the Nepali-Tibetan carpet is a fickle trend over which none of us have control. Just as Moroccan carpets were once popular in 1940s and 1950s America, they experienced a decline in popular consumption before their current resurgent popularity began in the early 2010s. As Western consumers have shifted attention elsewhere – to Moroccan, to Indian, to machine-made production – the relative and apparent modernity of the Nepali-Tibetan carpet has ebbed much the same way.

I do not believe Nepal can have a near-term resurgence in aesthetic popularity simply by revisiting the same types of designs nor are the ‘inexpensive’ prices of the past to return; assuming as we should that the Nepali-Tibetan carpet remain a unique handknotted carpet crafted of materials processed largely by hand. This latter point is the supreme strength of carpetry in Nepal and it must be maintained. Any maker in any place can make a cheap knock-off version of a Nepali-Tibetan carpet. Only Nepal can make what is now, genealogically speaking, the true Tibetan carpet. This is no different than it has been since rug making in Nepal was commercialized, but this distinction must now be exploited by the makers and exporters of Nepal. But how?

While many considerations exist, it is beyond the scope of this article to address them all. As such, three points of critical concern are addressed herein.

First and foremost, the industry must address the enduring concern of labour shortages in the form of weavers. It was a problem for the industry in 1999 and it remains one today. Secondly the industry must explore new aesthetics, new designs, new or revived textures – e.g. wangden – either in partnership with foreign buyers or developed internally with Nepali or Tibetan designers; these designs must likewise offer something new and unique to buyers otherwise they shall be overlooked. Moreover, these new looks must be in sync with the consumer demands of today. Finally, and this is perhaps the most difficult, the price paid for a Nepali-Tibetan carpet must be justified in the minds of the foreign buyer. This will require a collaborative marketing campaign that must come from the industry itself and it must extoll Nepal as the couture carpet making country it is.

One such pilot program that begins to address these concerns is the Artisan Villages Project by LabelSTEP and UKaid Skills for Employment (सीप) Programme.

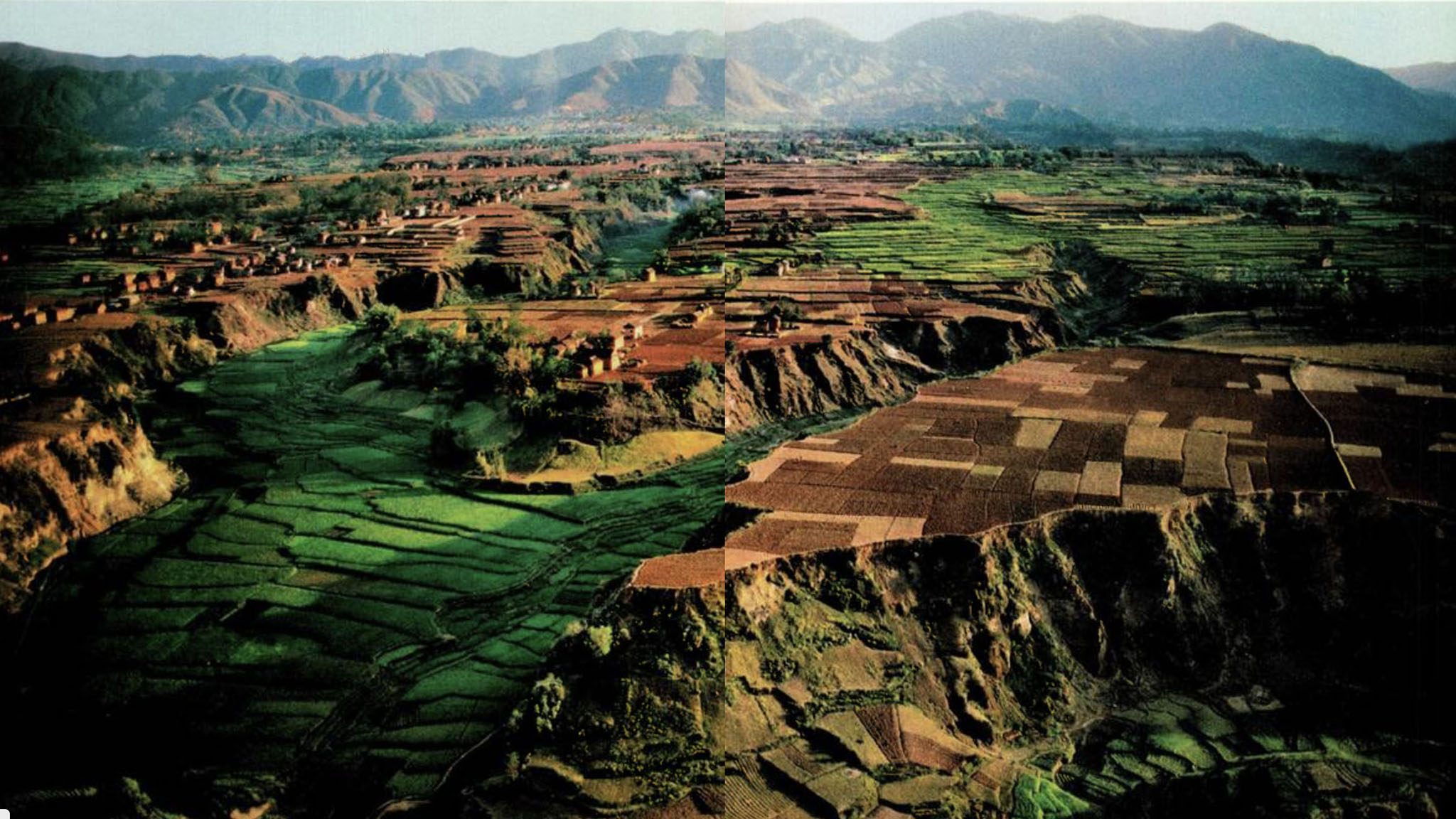

As described by Label STEP: ’For over fifty years, Nepal’s capital, Kathmandu, has been known as a creative and innovative hub of high-end contemporary hand-woven rugs. But the city’s booming real estate market combined with increasing international labour migration has put pressure on rug production facilities and led to weaver shortages. The once-thriving handmade carpet industry has become increasingly fragile. Artisan Villages are being set up in rural districts like Sarlahi in Province 2 where many of the weavers come from.’

The purpose of creating these villages of artisans and craftspeople is to develop state-of-the-art carpet workshops in these rural areas to help restore balance to Nepal’s carpet industry. More information about this specific project can be found here: https://label-step.org/artisan-villages/

As Kathmandu is no longer the lush green valley it was in the 1980s, rather a crowded and polluted city experiencing rapid grown and urbanization it makes sense to consider relocating production closer to workers. This has happened countless times in the West and it follows a pattern of urban development seen the world over. Moreover, given the communications technology of today it is now easier than ever to work in more geographically disparate regions. Relocation also allows for an improved quality of life for villagers without requiring them to add to the overcrowded nature of the Kathmandu Valley.

The Artisan Villages Project worked closely with Nepal’s own Alternative Technology whose Galaincha software has already been critical to the success of carpetry in Nepal. By fostering collaborative talent both domestically in Nepal and internationally, this project seeks to maintain the high standard of visual design for which Nepal is known. Furthermore, by training more individuals in Nepal to work as graphic designers this approach has the potential to cultivate a new creative class of Nepalis whose designs can compete with the likes of Western brands. This is not to say that Nepali brands will become known globally – perhaps they will – but it is to say the vast creative potential of Nepal remains under-utilized.

I truly believe that the best, most prudent course of action is one which involves some form of decentralization of carpet making out the Kathmandu valley into the bucolic rural landscape of Nepal. This will come at a cost, and it is one which must be borne not solely by aide agencies, nor government, but rather by partnerships with the industry itself and indeed foreign partners as well. To do nothing innovative is to languish with the status quo, continuing to ask the same questions and address the same problems that have agitated the industry since it matured to its current state.

From my experiences with members of the carpet making community in Kathmandu, I know the willpower, intelligence, and creativity is there to realize this rather significant change. Nepalis and Tibetans alike however need not pursue this on their own. Just as in the past, many foreigners – myself included – remain committed to helping along the way. From weaver to manufactory owner to importer, designer, and ultimately customer, a collaborative effort which brings to bear the combined expertise of everyone for the benefit of everyone should be a hallmark of any endeavour to transform rug making in Nepal.

While the Artisan Villages Project is just an example intended as proof-of-concept, I feel there is so much potential with this approach. Certainly it begins to address labour shortages by taking the work to the weaver and thus removing costs associated with bringing weavers to the valley, and it likewise has early beginnings at fostering creativity, but the real potential lies in what can be built new. For this is what prepares the industry for the future.

‘State-of-the-art carpet workshops’ are of course required, so too are dyeing and washing/finishing facilities that must likewise be state-of-the-art. In 2022 and beyond this means meeting stringent environmental and labour standards so as to protect the increasingly fragile environment of our mother planet. These are but a few examples of the countless facilities and infrastructure that must be built in order to re-locate production, but in short everything done anew must offer respect to our mother. Ama-la as I believe is said in Tibetan.

Finally, this approach also offers immense opportunity related to the marketing of Nepal as the preëminent maker of couture rugs and carpets.

While it is factual that the quantity of carpets exported from Nepal has declined considerably since the 1990s, the quality of carpets has perhaps never been better. And it is this high-standard which must be diligently maintained, cultivated, and extolled. Promoted on the world market as ‘simply the best’ not because of adherence to tradition alone, bur rather because these envisioned new carpets will have been made to the best practices and standards of this time and place.

High knot count carpets of immense complexity are now the standard of excellence by which modern carpets are judged, and innovative textures now also set a standard which others attempt to duplicate. Imagine then for a moment an entirely new rug making community in rural Nepal which meets social and environmental standards acceptable not just in Nepal, but the world over. Then make the best quality carpets, with the best quality materials, in the best environment possible, with the best social and environmental standards possible; in short, simply the absolute best of everything. That type of product is sellable – though not in the quantities of the past – because it addresses the needs of the planet, of workers, of manufacturers, and most importantly the needs of consumers who want a carpet unlike any other. That is how Nepal first gained prominence as a carpet making country and it is how it will regain prestige: by making what no-one else can. Don’t compete in a marketplace of mediocrity, rather lead so that others will have to follow.

The pandemic has taught us much and for me personally has caused me to question why we as humans seem intent on discussing the same problems over and over again. If weaver shortages were a problem in 1999 and remain one today, it stands to reason that we have simply not done enough to address the underlying causes of this problem. It is time to make a change which remedies this. Likewise the pandemic has taught us about resilience and adaptability, reminding us of the impermanence of everything.

At one time carpet making did not exist in Kathmandu, yet it experienced a period of great success – by volume – simply because it was willed into existence by a collaboration between makers and buyers. Those conditions no longer exist, but I, like many others, believe the conditions of this era offer new opportunities to build upon what has been learnt in this past half-century. As Brand Ambassador of Handmade Nepalese Carpets for the Nepal Carpet Manufacturer’s and Exporter’s Association (NCMEA) it has been and remains my honour to promote Nepali made carpets. I look forward to continuing this work with the NCMEA and likewise anticipate working with individual makers who might pursue a reborn industry outside the confines of the Kathmandu Valley.