‘And in the naked light I saw ten thousand people, maybe more. People talking without speaking. People hearing without listening. People writing songs that voices never share; no one dare disturb the sound of silence. ‘Fools’ said I, ‘You do not know silence like a cancer grows…” – Paul Simon

To write of rugs and carpets is to interject oneself into an esoteric world replete with a cast(e) of characters far to numerous to enumerate herein and from my decidedly privileged Western experience it further seems as though each of those characters has at least one (1) opinion on any rug topic imaginable. Thus it is when choosing to discuss a particular topic or specific rug, one has to decide not only one’s own thoughts on the matter, but also the approach and tone of the article. Is the discussion serious or irreverent? Yes. Does it – as has on occasion been the prerogative of this author – examine carpets with an eye toward pure design; a faux reality of aestheticism in which meaning is lost in favour of the ephemeral and obsolete, planned or otherwise? Perhaps. Does it examine a carpet with the mindset of the purist capitalist discussing the maximization of profit through euphemistic phrases such as ‘value engineering’ or does one ponder the importance of handmade in an age when mechanization through robotics encroaches continuously, eroding the shores of craft? Does it, does it, does it ad nauseam? Absolutely. For you see, when discussing merits outside the scope of technical carpetry*, there is rarely one correct answer. Unfortunately we have collectively allowed the arbitrary rules of subjective discussion to invade the realm of objectivity through our complacency; a dangerous development not confined solely to the world of rugs and carpets.

And so it is then that The Ruggist presents the provocative and profound carpet collection from Nasser Nishaburi: ‘Silence Azerbaijan’

Nasser Nishaburi’s family is from Tabriz, both the historic capital of West Azerbaijan with an ancient culture and a place-name familiar to many insomuch that the moniker persists – as a hallmark of quality – in rug and carpet design regardless of geographic origin. In the words of Nasser Nishaburi: ‘My ancestors have been weaving carpets and trading there as exporters since 1750. The name Nishaburi was given to us due to the extensive trade that they did with the East through the Silk Road on which the city of Nishabur was a major stop. What we produce in Tabriz is a continuation of an old tradition that is intertwined in my soul and strongly responsible for my love for rugs.’ To say tradition informs the work of Nasser Nishaburi is to speak in understatement.

Of course, one’s family does not go about the business of carpetry for over two and a half centuries by remaining rigid and unchanged at least when the topic is of aesthetics. The commitment to traditional means and methods of weaving on the other hand could be best described as, puristic, revivalistic, even fundamentalistic if focus remains on the craft of carpet making. But this is not a discussion of the technical, rather it is a discussion of ‘Silence Azerbaijan’ in the context of its presentation as ‘the meeting point of old and new, tradition and modernity.’ to quote from the firm’s own literature.

‘We city peddlers were taken by surprise by the quietness in the home, the calm in the villages and the profound silence in the workshops. The omnipresent silence grasped our attention, the silence and the rhythmic and steady movement of the weavers. Sitting in a simple crossed leg posture an ephemeral dance right to left, left to right guided the dorsal spines whose hands were flying through the warp. Azari weavers at ease, keeping themselves to their thoughts in a meditative attitude, concentrated on their execution of the design.’ – Nasser Nishaburi brochure presenting ‘Silence Azerbaijan’

As the firm further poetically waxes ‘Absence of Words, Absence of Sound, This is the Beauty of Silence.’ one remains hard pressed to argue against the healing, restorative, and meditative power of silence, yet the design is evocative of more. For those who profess the supremacy of handmade carpets as ‘true art for the floor’ this then asks the eternal question of: ‘What is art?’ For many, especially amongst those who feel the painting should match the sofa, this is a simple discussion of aestheticism and aesthetics. ‘Is it pretty?’ and ‘Does it make me feel good?’ This is the arguably unfortunate state of commercialized rug and carpet making today. Across all qualities of construction from inferior and poor to the crowd pleasing cheap-and-cheerful to the homogeny of mass produced prêt-à-l’achat to the allure of couture boutique brands there exist literally endless consumer choices; many of which purport to be art, dubious as that claim may or may not actually be.

Without doubt it takes skill – of various calibers – to produce any handmade rug or carpet and thus undisputed in this argument is that all rugs and carpets are craft. However, just as not everything found at a farmer’s market or weekend craft fair is art, so too must we apply this same logic to carpetry.

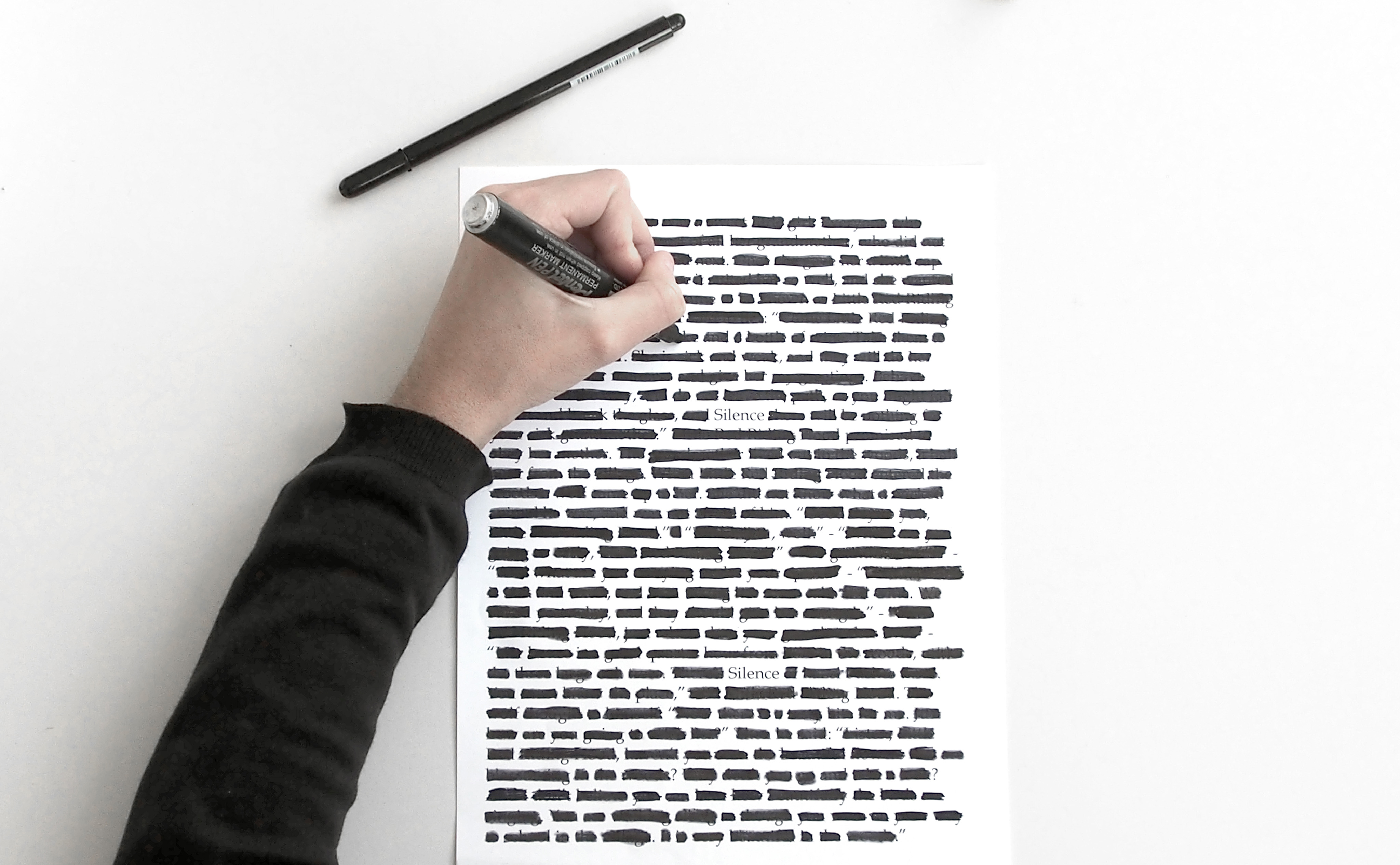

Luis Eslava designed ‘Silence Azerbaijan’ for Nasser Nishaburi and while he is no trained carpet designer his philosophy that a designer must be able to ‘Rethink daily life.’ resonates perfectly with not only a handmade industry at historic crossroads – new and old, tradition and modernity, hand versus machine – but also with societies and cultures the world over facing change in unprecedented ways. To invoke all too familiar contemporary imagery of secrecy, of silence against the truth, as a statement against this immemorial society-plaguing problem is to provoke thought, radical or otherwise, as all true art must.

‘Silence Azerbaijan’ is transcendent work.

That is subjective opinion and while for the sake of brevity this article will forgo a lengthy discussion of geopolitics, economic theory, societal expectations, et cetera it is imperative to examine the contradictions and juxtapositions embodied therein. From an objective perspective there are innumerable examples the world over of governments and institutions, of those in control, who would rather the vox populi be discreet, silent even, if extant at all. Western governments would have you believe this is a problem confined to places such as Iran where this collection is made, but for those with access to information and critical thought, the problem is widespread and the truth is unfortunately far more nefarious. Silence against injustice, against lies, against the Orwellian, is a universal problem. To then examine ‘Silence Azerbaijan’ as the seminal work of twenty-first century carpetry in the calm and silent meditative mind is to realize the unbridled power of silence, constructive, destructive, or otherwise.

The interpretation of [text redacted] into a carpet design invites discussion such as this. It poses the questions that must be asked, and it begs those who choose to remain silent not for fear of retribution but because of complacency to shed these irrational fears. Do you like the carpet? ‘Speak your mind!’ for in this subjective regard there is unlimited room for debate and discussion, but what if the questions then turn toward the objective? ‘Speak the truth!’ for in the dominion of truth and fact there is but one truth, its versions, mis-truths told through biased lenses of perspective. ‘Silence Azerbaijan’ calls upon all who value both the art and the craft of carpetry to speak out with passion and with truth, not only in regard to the recondite nature of rugs and carpets but in all manner of existence. Simultaneously a bold artistic statement and a sublime carpet which, if one were to interject a bit of irreverence, also matches the sofa, ‘Silence Azerbaijan’ masterfully expresses a proverbial thousand words with nary a sound… …of silence.

*carpetry: While there are scant English language references to this term save for a few names of products which incorporate traditional carpet motifs, I first heard the term on 3 October 2017, during the Second Annual Istanbul International Carpet Conference held during Istanbul Carpet Week. Professor Günay Atalayer from Marmara University in Istanbul presented on ‘The importance of structural analysis.’ and it was in the live English interpretation of her Turkish language presentation that the term was heard. Is it ‘correct’? Who cares! Language evolves and if carpentry can describe ‘the craft of a carpenter’ so too can carpetry describe ‘the craft of a carpet maker’.