In the 1999 film ‘Dogma‘ Salma Hayek plays ‘Serendipity’. Not simply a woman whose name happens to be Serendipity, but rather she plays the physical embodiment of serendipity itself, which is to say she is the ‘chance’ which brings about the occurrence and development of events in a happy or beneficial way. Except of course, there is no chance. While those without divinity perceive their interactions as random, or due to fate, or karma, or what have you, from the perspective of Serendipity, it is her will which causes events to happen as they do; for her the future is not fully unknown nor fully manifest rather its exists as any one of an endless number of permutations based upon her direct actions. In many ways the creation and success of a supposedly new rug or carpet design is a result of serendipity with the artist or designer creating something perceived as new as a result of the careful and equally serendipitous or Serendipitous work of those who have come before.

‘Nothing dulls faster than the cutting edge.’

Unknown

Copyright is a topic of great debate and conjecture not only within the world of rugs and carpets but in the creative world broadly. Acrimonious discussion over who first – as opposed to best – designed something, who is a copyist – an odd word tinged with subtle derogatory connotations – and who – from the perspective of those who were first and thus also copied – should not be ‘allowed a public platform to show the work’ to quote COVER Magazine Editor Lucy Upward in her missive ‘Copyright!’1 Throughout the last several years, including a co-authored article with now Executive Editor of COVER Magazine Ben Evans2, The Ruggist has written directly on the subject of copyright no fewer than seven times and made countless references to the topic in articles on a variety of subjects. In short, it is a subject about which I am passionate, relatively well read, and thoroughly thoughtful. Broadly speaking it is also one the rug and carpet industry prefers to keep swept under the rug. Upward’s thoughtful commentary was serendipitous insomuch that the topic had already been returned to rumination by events including but not limited to the very same Jan Kath incident reported to COVER which instigated Upward’s article.

‘If the iron is blunt, and one does not whet the edge, then more strength must be exerted; but wisdom helps one to succeed.’

Ecclesiastes 10:10 Note: The inclusion of a passage from the Christian Bible is not an endorsement of Christianity over any other religion. In fact, it was chosen out of convenience and expedience as the prophetic message contained in its poetic verse is apt to this discussion.

A dutiful thinker must now ask: ‘Is not this article on copyright some kind of copy of Upward’s piece?’ Yes and no. ‘No’, because this text is not taken verbatim unless indicated by quotes and citation. ‘Yes’, because it is about the same topic, the same idea. It is this erroneous conflation of idea – not covered by copyright – and execution – covered by copyright – which plagues discussion of copyright not only in the world of rugs and carpets, but in the entire creative sphere. Dare the notion of colour, a matter not protected by copyright but oft erroneously included, be considered and the lively debates between originators (those who are first) and copyists (those who are followers) can become heated and passionate, if not also burdened by error. But to what end?

Personally I understand and appreciate the message Kath is telegraphing and I have nothing but the utmost of respect for both him and Lucy Upward, a person I consider a friend, colleague, and now competitor of sorts. That notwithstanding, this essay in consideration of copyright does not carte blanche support creators nor does it fully denigrate copyists. It presents counterpoints to several untenable assertions and it is offered as a realistic voice which acknowledges the tacit reality that this, all of this, all that man has, and will create is based in one way or another on copying. This is not to say one should directly copy the work of others – how uninspired – but it is to acknowledge the foundations of civilization.

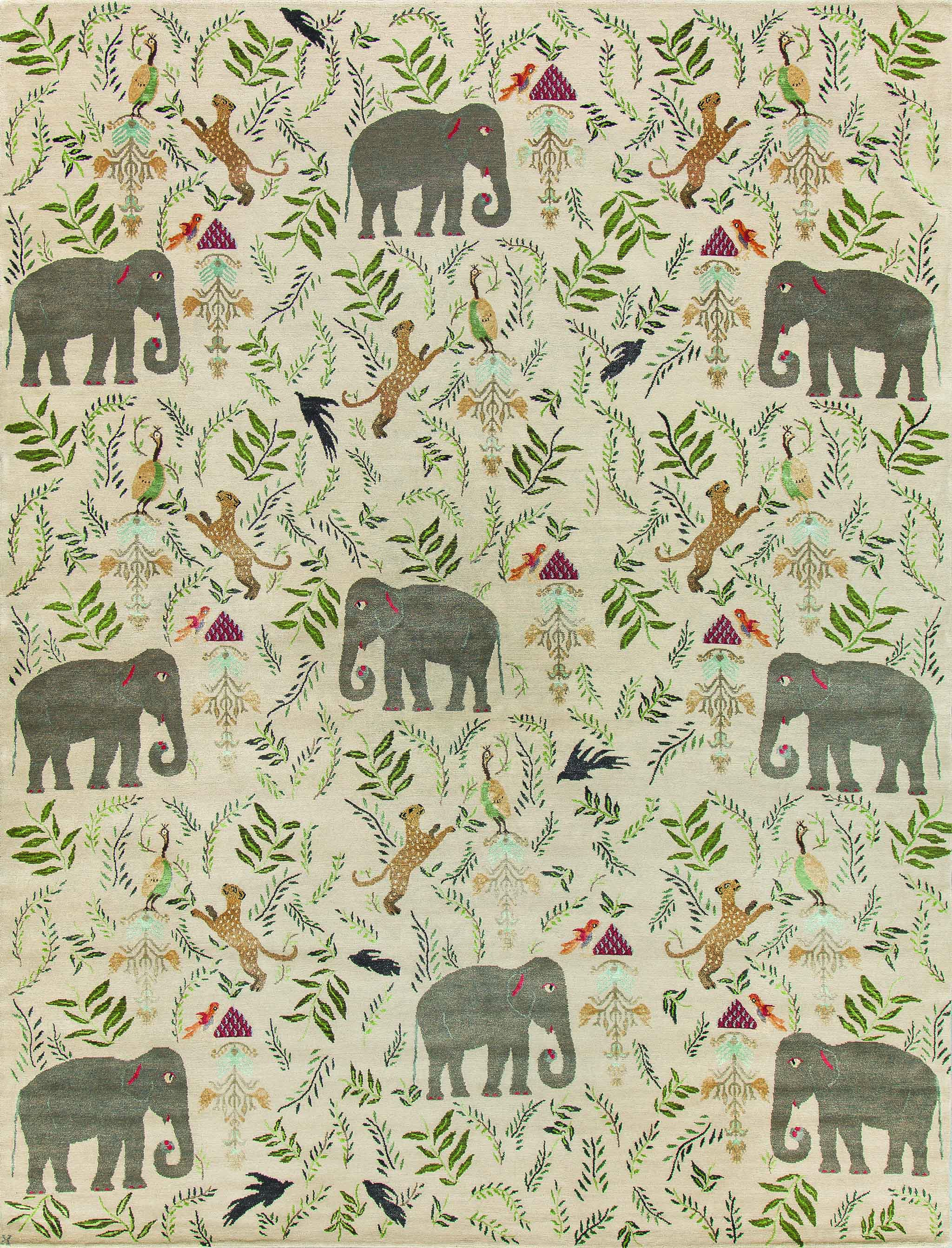

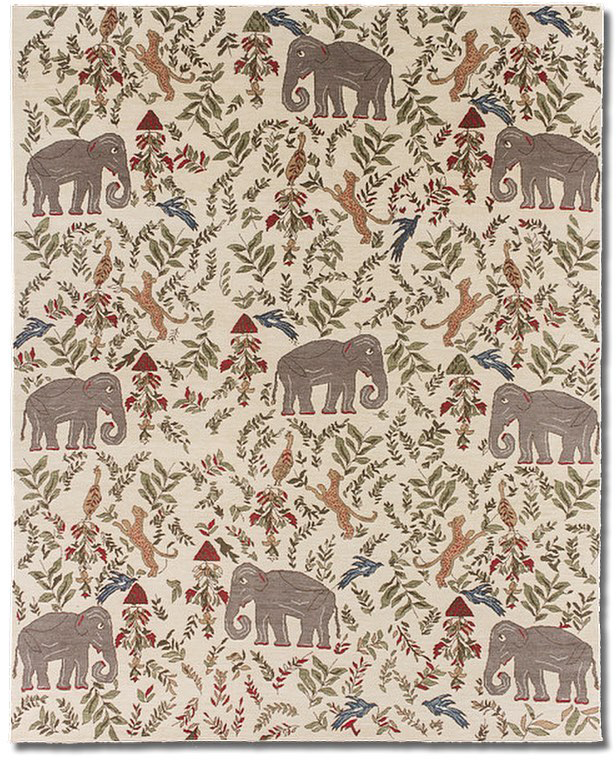

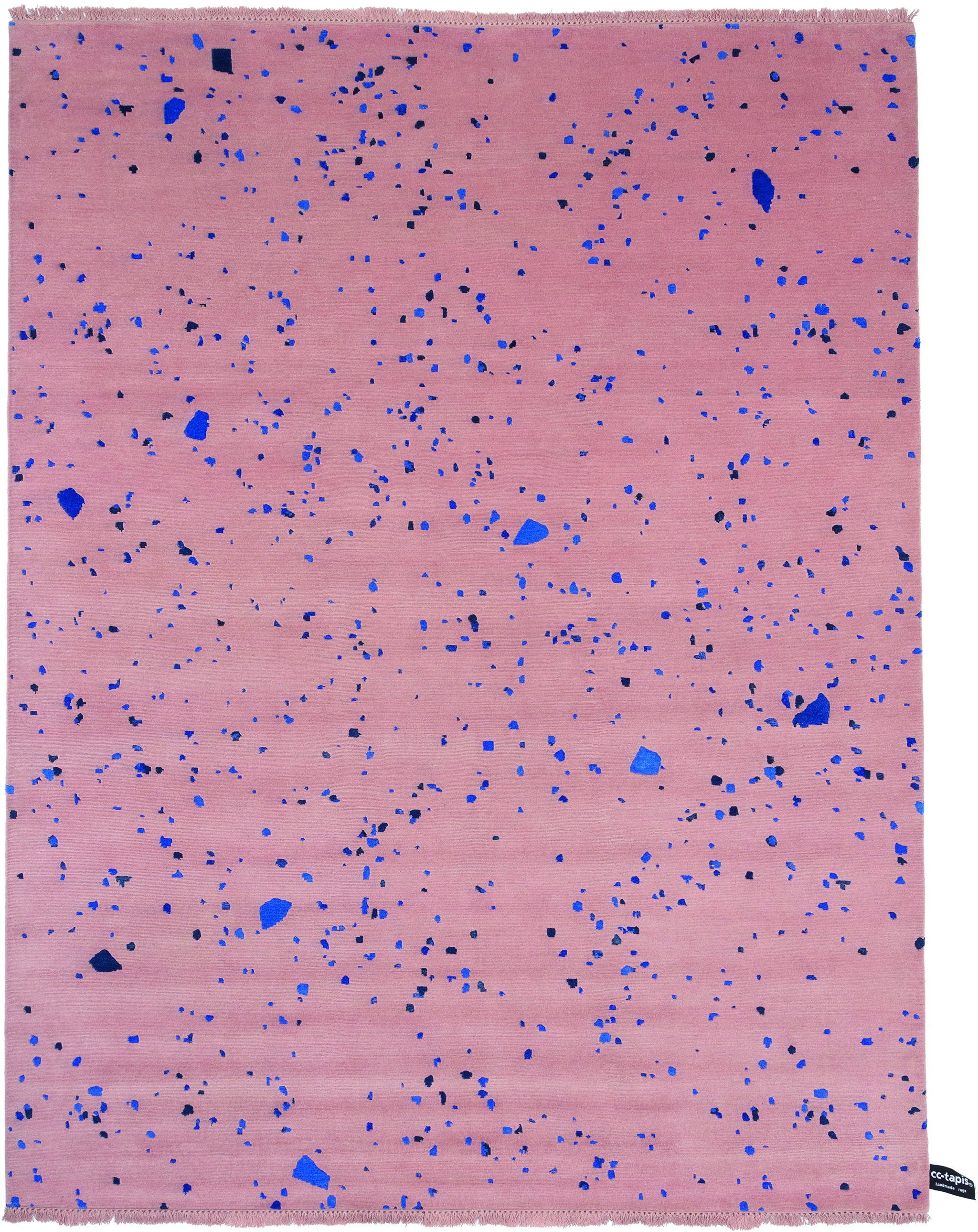

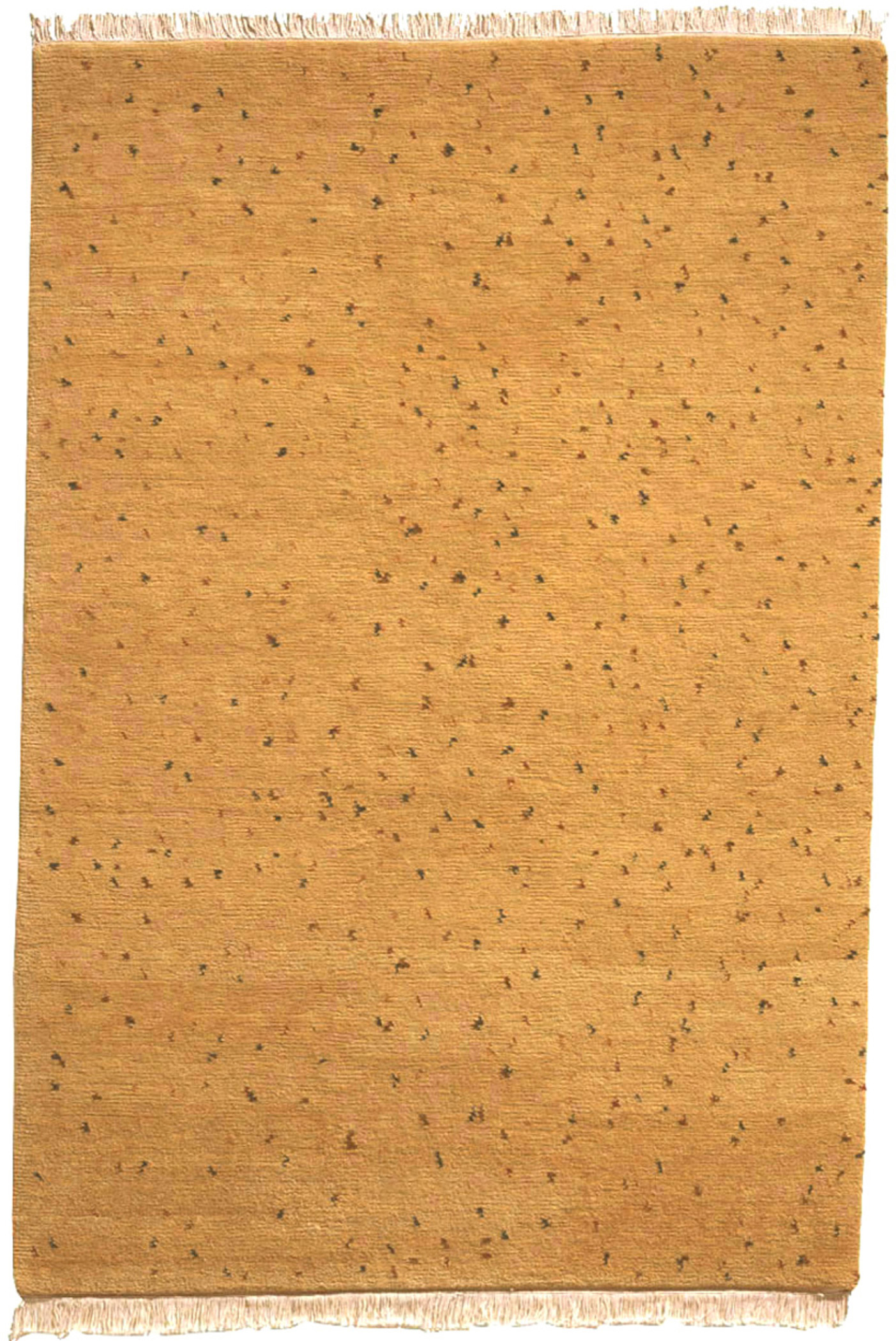

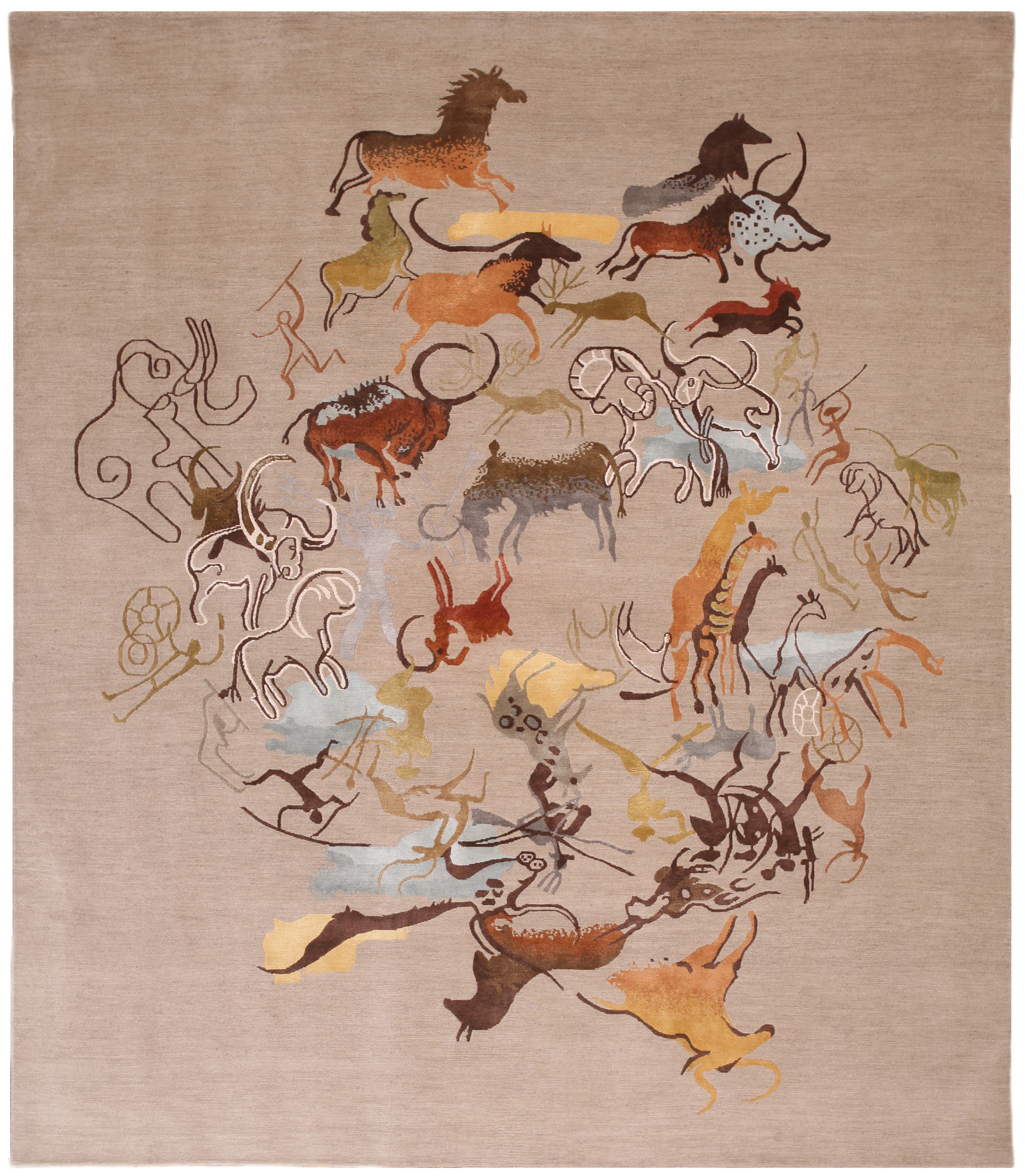

One such ‘event not limited to’ Kath’s was the discovery on social media of the above knockoff created expressly for Sharon Schenck of Nola Rugs in New Orleans, Louisiana. Dissect and argue the minutiae of differences betwixt the two carpets ad nauseam but it will not change the fact visible to anyone with eyes that the knockoff is intended to deceive the casual or ordinary viewer into believing the knockoff is genuine.

Rather incensed by the situation – for I do strongly believe in protecting original work for discrete periods of time – I commented on the original Instagram post – now deleted by Nola Rugs yet preserved herein – noting the lack of refinement in the knockoff – a common trait of the form – making reference to my original article on the delightful ‘Menagerie‘. Numerous attempts to elicit comment and clarification via direct message and email from Nola Rugs – who has since blocked @theruggist on social media; a common trait of the sarcastically innocent – were made to no avail. In faux defence of the offending party perhaps they only purchased the rug rather than commissioning it, but that is not what was said and informed or even ordinary consumers must take their word at face value. Said another way: Nola Rugs and Sharen Schenck duplicated – perhaps illegally – the work of New Moon and then bragged about it on social media.

This is the most egregious form of copying, the one which infringes, the one worthy of the pejorative undertones of copyist. It is also the type Kath calls to attention and the one Upward audaciously stands against stating, ‘We [COVER] will never knowingly publish a copy or something that we deem to have move [sic] beyond being merely derivative, and will not work with companies that do not promote original design.’ If only it were that easy. Spoiler Alert!! It’s not, and as of the February 2025 edit of this article, COVER still does business with Rug & Kilim and French Accents. Keep reading…

As it stands today modern copyright law is an anathema to the long term creativity and autonomy of our human civilization. While I support without hesitation the concept of copyright for reasonable periods of time, the current global standard of forever3 is an absurdist’s – derogatory connotations intended – attempt to control the near future while simultaneously exploiting the equally as near past. It would be laughable if the consequences were not so ridiculous. In ‘Märta Måås-Fjetterström’ which appears in the Summer 2018 issue of Rug Insider Magazine, trend expert Stefan Nilsson laments: ‘But why now? Some say Mid-Century is a trend because at that time we had a different relationship to say color. Others say the rights to original period designs are now lapsing which means that the rights are basically up for grabs; anyone will soon be able to reproduce a chair from the 50s, for example. Whatever the reason, I feel as though a good portion of the last twenty years has been spent endlessly revisiting trends and styles from the past without regard for developing a true style of this time.’ And why is that? Copyright.

Prior to a change in United States’ law in 1978 C.E. – the year the Copyright Act of 1976 took effect – most works were afforded copyright protections for twenty-eight years with the option for a single renewal. Afterward protection was extended both retroactively and to new works for terms which amount to life plus seventy-years (or more). If this sounds repressive, it is, as it restricts the ability of others to create new work on the past work of others – a hallmark of innovation and advancement. In its stead a copyright holder – including somehow the seemingly perpetual estates of dead people – need not create anything new, anything fresh rather they may coast on previous successes with little fear that a copyist or even a derivatist (one who derives) might somehow outdo their original work. This is how copyright currently works in industries flush with cash and attorneys and set in Western countries. It is also reflective of a conservative repressive ‘corporations should own it all forever’ mindset indicative of this time. Yet for decorative industries dependent upon the developing world – no matter the uninspired nature of direct copying – daily concerns are more visceral and temporal, less dynastic.

Kath and others are correct to be concerned when someone directly and illegally copies their work, but philosophically speaking: How can creators of this period adamantly stake claim while simultaneously either deriving or copying the work of others from the past? If copyright terms were returned to a succinct timeframe – I advocate a twenty-one (21) year term – then this would not be a problem. But when a rug design could be created today and not become public domain, and thus able to be copied or derived from, until perhaps the year 2178 C.E. only an intentionally obtuse person would argue this spurs creativity. On the contrary, these extended terms slow creative development by restricting information to a privileged class much like civilization prior to the invention of the printing press or the internet. Progress is fuelled by the spread of information – or design – and copyright is intended to allow those who create to exclusively profit for discrete periods of time, not what is for practical purposes forever.

This assertion is contrary to Upward’s who states: ‘Copying of original works is highly detrimental to the rug industry. The greater the issue of copying becomes, the more likely it is that leading brands and designers will stop producing and innovating at the top end of the market, reducing the viability of the whole market.’4 With the utmost of respect to Upward, I beg to differ and will equally as audaciously assert this is incorrect. Copying does not force those who innovate to stop innovating. The lack of outward pressure to improve, to create new, to remain at the vanguard – the cutting edge, allows – through complacency – those who had formerly been originators to become blunt and dull; choosing to rest upon their former laurels instead of looking for new heretofore unseen heights.

Take for example the formerly mighty rug firm of Asmara. Whether known or otherwise Asmara was at one point in the oughts a leading rug company in the United States, renown for their remarkably well executed needlepoints, Aubussons, and Savonneries which remain exemplars of that form of the art of carpetry. The firm was widely copied, in turn devoting considerable resources to protecting its copyrighted designs. This did – as Upward asserts – prevent them from creating new innovative carpets as the mental and creative resources of the firm were more concerned about the past than the future. Instead of continually redefining themselves at the cutting edge, they allowed themselves to be dulled, and dullness kills a fashion driven business faster than one can say passé. Blame lies not solely with those who copied, but also those who failed to remain relevant, or sharp, and primarily with those who actively choose to buy copies instead of originals.

In order to remain a leading brand or designer, a firm must continue to lead. It does this by continually remaining sharp. The whetting process removes and refines the dullness, returning the cutting edge, whereas repeating the same process over and over without refreshment, without whetting or perhaps even only honing, only leads to dullness and more exhaustive effort in an attempt to achieve the same now unobtainable goal. Bluntly speaking, if a fashionable leading brand wishes to remain so, it must continually look toward what is perceived as fresh and new not toward what has worked before. Think literally of a dull kitchen knife – the aforementioned blunt iron. A sharp cutting edge will produce beautifully sliced tomatoes without effort, whereas a blunt or dull edge requires significant effort to produces slices barely worthy of the descriptor. It is no stretch of reason nor imagination to assume those who lead would rather craft beauty.

Serendipity, by definition, requires a happy or beneficial outcome and as such it seemed appropriate for this discussion of innovators and copyists as the success of either party is based upon a confluence of mystic forces unknowable to those without divine insight and perspective: the fickle whims of consumers. While there may have existed a time when rugs and carpets where fashionable yet not fashion driven, that time is not now. The consumption of carpets, as part of the broader home furnishings market, is driven by a host of socioeconomic factors as well as the tastes, self-realized, sheeplike, or otherwise of consumers. It is serendipitous when a design resonates with consumers – as opposed to critics for what do they know – yet just as quickly as the flock may embrace, it may turn toward something else entirely. In the context then of copyright, what good does control over a design forever do when consumers now no longer care to buy it?

There is a degree of untenability in regard to modern copyright law which reeks of regressive politicking, of a minority seeking to control the will of the masses. Those who aggressively assert copyright seem to inevitably falter under delusions that their pre-existing, perhaps at one time leading work is going to sustain their position at the top even in the face of ever shifting consumer whims. Again, it is worth rhetorically asking: ‘What good does control over a design do when consumers no longer care to buy it?’ Try as one might, it is veritably impossible to force consumers to buy something no longer considered fashionable no matter the reason.

This discussion reminds of those which take place with the passing of each generation. ‘Millennials are killing the [WHO REALLY CARES THE ARTICLE WAS JUST CLICK BAIT PAID PROPAGANDA TO TRY AND SELL MILLENNIALS SOMETHING THEY DON’T WANT] industry.’ Conversely the same Millennial is asking: ‘Why aren’t companies selling what I want to buy?’ Scapegoating is a long held human trait and while no-one stands accused of doing as such, it is wise to acknowledge there are at least two perspectives related to copyright.

Understanding this requires the ability to see beyond the increasingly intimate confines of niche carpetry, beyond those who cater to the attuned, to see the entirety of the rug and carpet industry including but not limited to: handknotted, handloomed, flatweave, handtufted, tufted, robotufted, printed, woven, machinemade, so on and so forth from tippy top to dregs. Bold and moral as Upward’s statements may be, perhaps it wise to recall the sage words of Wendell Johnson first quoted by The Ruggist on 18 December 2008,5 ‘Always and never are two words you should always remember never to use.’

‘I can’t recommend what I can’t defend.’

‘Doom or Destiny’ by Blondie, Debbie Harry

Therefore I cannot recommend carte blanche absolutist statements forswearing future business when within the same issue and then the Summer 2018 issue of COVER, and indeed in innumerable issues since, therein are examples of inspired or copied work difficult, if not impossible to defend. I say this not as a critic of Upward’s but rather as the former Editor of a ‘competing’ magazine, Rug Insider, which historically and currently features rugs and carpets from across the market spectrum, including many which could be considered copies in some way of those at the leading or cutting edge. It’s simple economics and the big budge of consumers in the middle – the ones who cannot or choose not to afford the recherché – enjoy style as much as the next person, even if it is perhaps less refined. It reminds of the jocular words of Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother who in the 1970s in reply to advice not to employ homosexuals in the Royal Household, said: ‘We’d have to go self-service.’ Likewise, who would we – that is any of us – write about and do business with if we adhered strictly to Upward’s ideal?

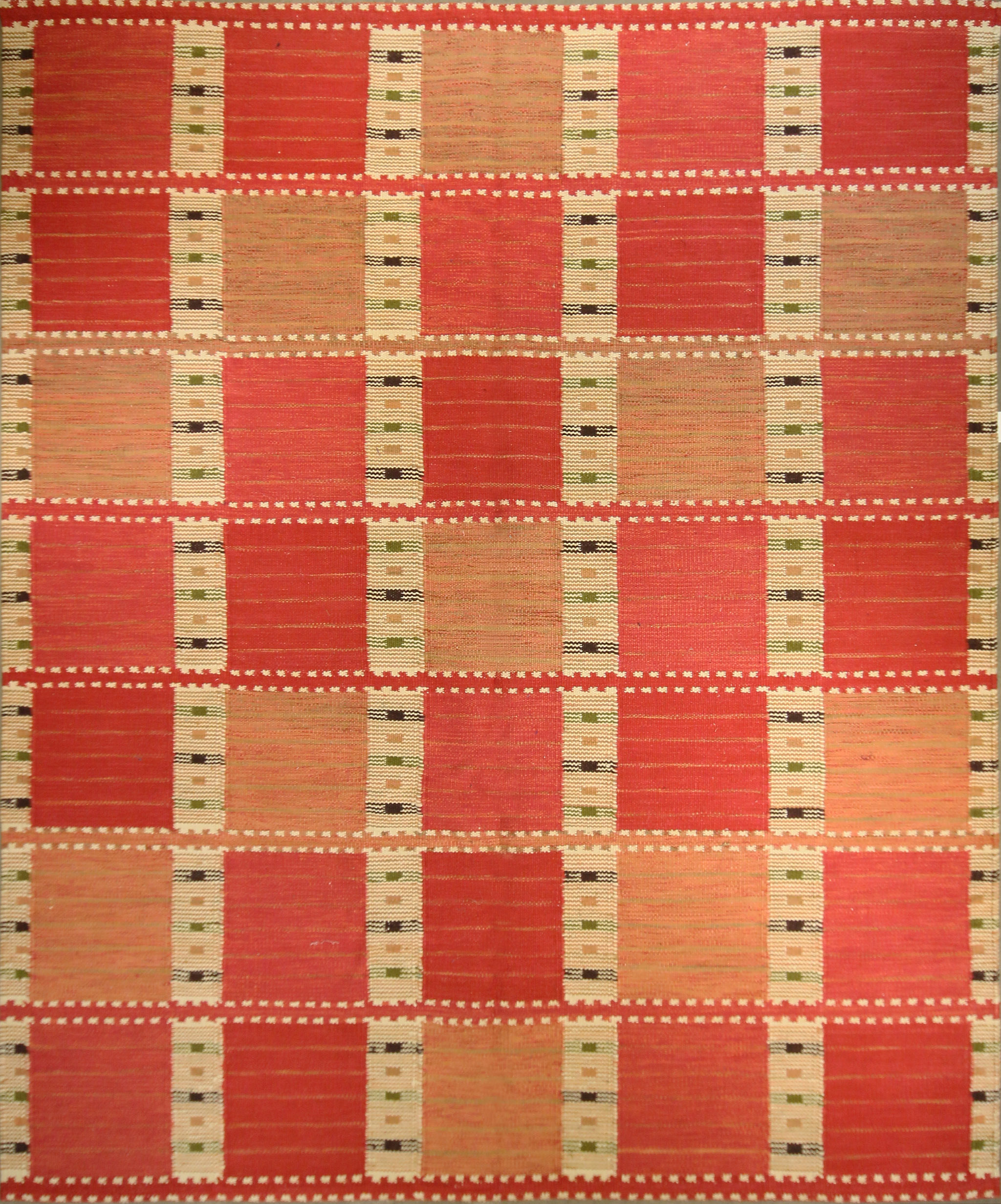

Unmentioned thus far are the myriad examples illustrated herein of rugs and carpets which bear remarkable likeness to one another. Carpets such as those from French Accents and Reuber Henning, or cc-tapis and Odegard [Note: This pairing is discussed in intimate detail including copyright in the Winter 2018 Issue of Rug Insider in the article, ‘The Cycles of Design’], or Werner Weber and Odegard, or Jan Kath and Knots Rugs appear to be related – perhaps cousins – but not copies per se. Conversely the carpets from Rug & Kilim and Märta Måås-Fjetterström, and Olga Fisch and Rahmanan Antique and Decorative Rugs are decidedly more alike than dissimilar. The former grouping foreshadows a development in the world of rugs and carpets most in the industry have not yet imagined while the latter speaks to issues complex and unresolved.

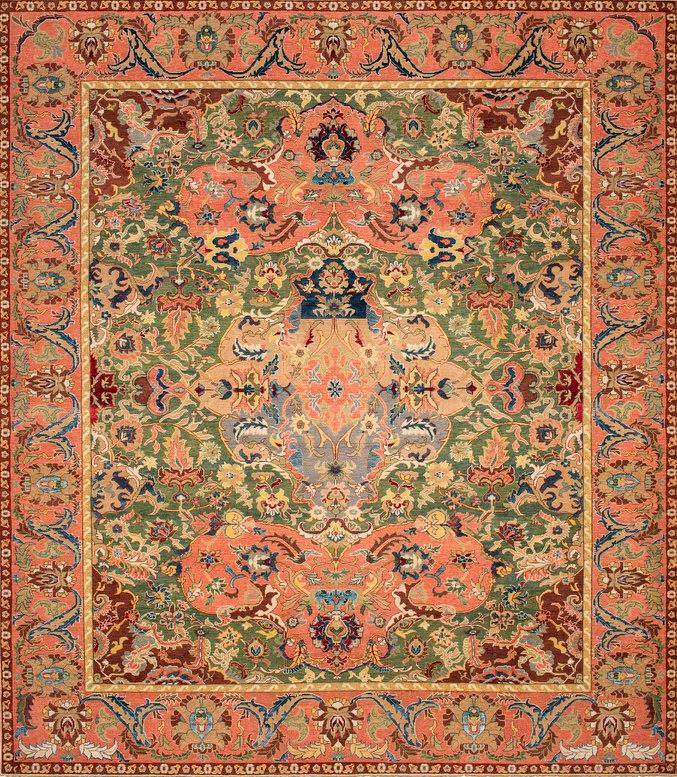

Best illustrating the purported unimagined development are the Jan Kath and Knots Rugs Polonaise carpets. Neither firm originated the Polonaise style, nor are they the first in the modern era to reproduce the noted 16th and 17th Century Persian carpets. The lens of history does not distinguish between the first, or second, or third, ad infinitum Polonaise carpet made at the behest of Shah Abbas, just as it likewise does not distinguish between Heriz, or Tabriz, or Aubusson, or ad infinitum, with one exception: intrinsic quality of execution. No serious person would say one period Heriz is a knockoff of another, just as no serious person would say Jan Kath’s modern copy (and improvement?) of the form is a knockoff of Knots Rugs’ even though it has come afterward. As the modern carpet era has now matured it is time to seriously consider examining the carpets thereof with less of a marketing and advertising (read: corporate propaganda) mindset, replacing it with one more academic.

These – and the originals – are all Polonaise carpets, and some are and shall remain better than others, just as some of the modern versions are better than others, and some Heriz are better than others, and, and, and. As the other related carpets illustrate there are many distinguishing characteristics and similarities – beyond the sophomoric modern, traditional, transitional and the like – which beg even an ordinary observer if so tasked, to group akin carpets. As such, it is time to assign genres or classes of contemporaneous carpets just as there are genres such as Tabriz of carpets more aged.

The latter grouping of carpets is more complex and pushes dangerously close to infringement. In the case of the ‘Caverna’ reproduction by Rahmanan Antique and Decorative Rugs the firm made a differently sized carpet than the original period Olga Fisch carpet they owned. In the case of Rug & Kilim, the intent to duplicate the look of period Märta Måås-Fjetterström rugs is unquestionable. In both of these instances the firms whose work is being copied are still in business – yet pursuing different markets and product categories – prompting questions such as one New Moon, or Jan Kath, or anyone might ask: ‘But what can be done?’ or one I would ask: ‘How is society served and advanced by affording copyright protection to long deceased designers?’ as is the case in both of these examples.

It starts with the open acknowledgement that we are all at fault. Period. Anytime someone such as Schenck copies and we say nothing, the copyists win. Anytime one walks by a stand at a trade show and does not say anything about the knockoff, the copyists win. Anytime a consumer of any level willingly chooses to buy a knockoff, the copyists win. And in this instance it is worth mention that it is not just end consumers to blame, but also unscrupulous traders who seek a lower price, intentionally seeking to undermine those who create, such as is apparently the case with ‘Menagerie.’

Upward’s key point, one which should resonate with everyone is that if society is to value work, then society must value work by ‘buying original’. Period. Otherwise, through our collective complacency and inaction we become collaborators with the copyists; a position I argue we are already in and it’s not confined to rugs and carpets.

Likewise, we must also collectively acknowledge the difference between copying a design and copying the idea of a design, or for that matter a colour. We must call out the copyists to protect the originators but we must also defend derivatists from originators who have not exclusive domain over concept. Perhaps the most expeditious and timely example is that of the Spacecrafted carpets from Jan Kath. Only that firm can make the exact carpet shown above, yet anyone can be so inspired to take a photograph of space and render it as a carpet. This is not infringing, this is inspirational, and while it is copying of sorts (of concept), it is not egregious nor detrimental. It is simply how humanity has progressed to this point; by forcing those with genuine talent to remain sharp, serendipitously or otherwise.

Further Reading

For those looking to delve even deeper into my thoughts on copyright, consider reading these past musings:

- Copyright This!

- Copyright This! Again?

- Exploring Copyright

- I want a Knockoff! | Paul Smith Rug

- No Euphemisms, It’s a Knockoff!

- Copyright Footnote!

- Modern Carpet Design | Galaincha

- Empire in Retrospect | UK Heritage Rugs

- Interwoven Authenticity | A Caveat

Footnotes

- ‘Copyright!’, COVER Magazine, Spring 2018 Issue, pages 40-41. ↩︎

- ‘Copyright!’, COVER Magazine, Winter 2012 Issue, pages 66-69. ↩︎

- ‘Copyright Footnote!‘, The Ruggist ↩︎

- ‘Copyright!’, COVER Magazine, Spring 2018 Issue, pages 40-41. ↩︎

- ‘It would have been a ‘Year in Review’ but I’ve only done this for six months…‘, The Ruggist. ↩︎

Nota Bene: This article was originally published 2 July 2018. It was edited in February 2025 to update certain details.