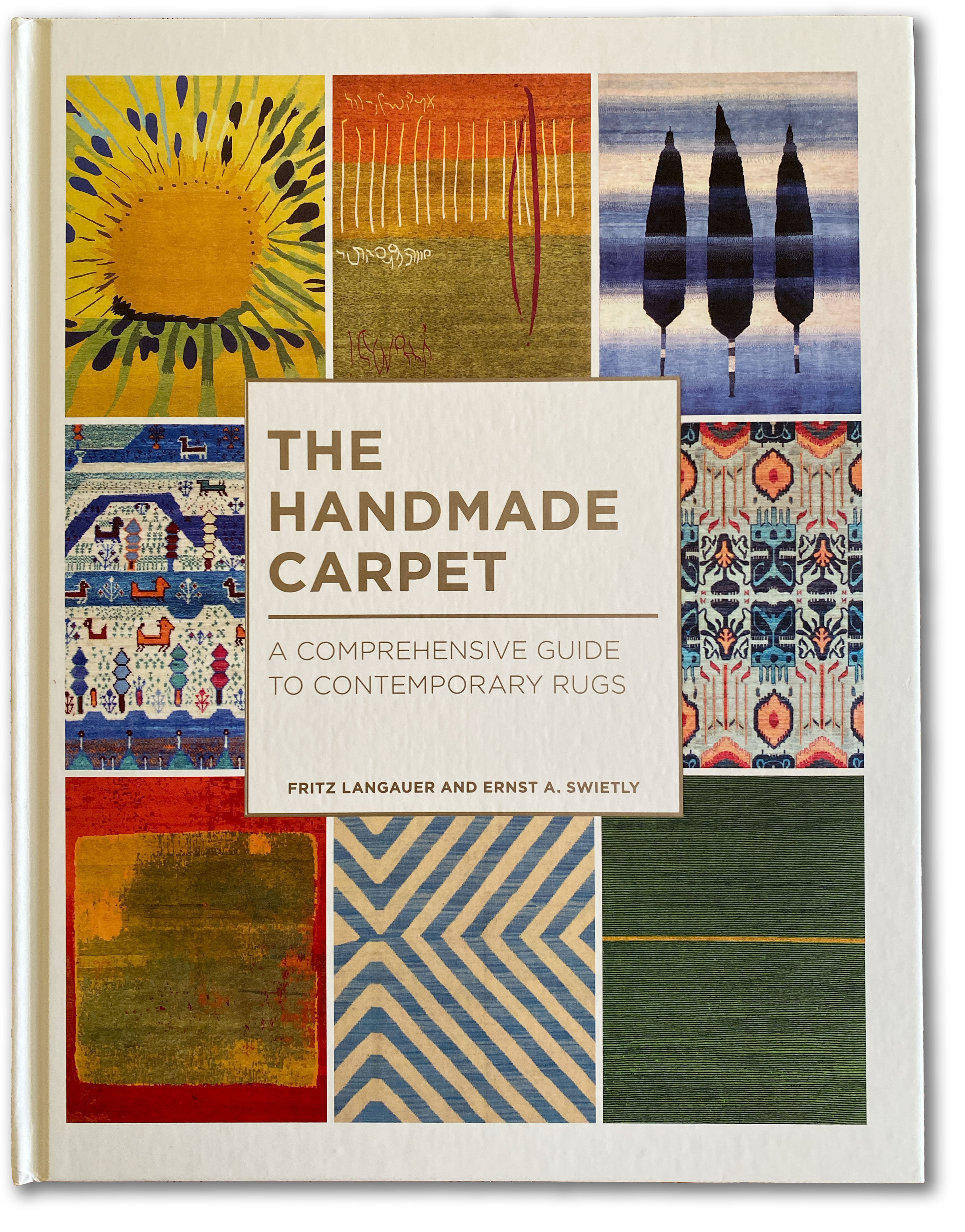

The nearly three-hundred pages of text and imagery of ‘The Handmade Carpet’ contain a wealth of knowledge accumulated over the long and storied careers of the authors Fritz Langauer and Ernst A. Swietly. The assertive authors undoubtably put forth superior and exhaustive efforts in compiling what amounts to multiple lifetimes of experience, information, expertise, commentary, and so forth as they attempt to explain, as the subtitle of the tome – ‘A Comprehensive Guide to Contemporary Rugs’ – purports, contemporary rugs and carpets. In the final analysis however, it must be stated that while the volumn is indeed comprehensive in regard to certain aspects of contemporary carpetry, it likewise lacks in its treatment of contemporary as the word has come to be employed in the colloquial of today.

Perhaps it is a matter of vernacular but for the casual observer of rugs and carpets and even the seasoned expert, contemporary has developed – as all language does – to mean more than ‘happening, existing, living, or coming into being during the same period of time1;’ particularly within the confines of the decorative arts within which handknotted rugs and carpets produced since the pænultimate fin de siècle undoubtably exist. Now generally denoting a quasi and poorly defined style akin to modern – itself a term increasingly made vague by the peculiarities of marketing, advertising, and propaganda – it seems to this stern and discerning critic that the authors would have been wise to directly address the notion of contemporary as more an aesthetic concern than temporal; for it is my fear the reader who assumes the former may be disappointed by the latter.

‘All that glitters is not gold;

William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice, Scene VII, Belmont, A room in Portia’s house.

Often have you heard that told:

Many a man his life hath sold

But my outside to behold:

Gilded tombs do worms enfold.

Had you been as wise as bold,

Young in limbs, in judgment old,

Your answer had not been inscroll’d:

Fare you well; your suit is cold.

Cold, indeed; and labour lost:

Then, farewell, heat, and welcome, frost!

Portia, adieu. I have too grieved a heart

To take a tedious leave: thus losers part.’

For the would be reader of ‘The Handmade Carpet’ be prepared to step initially into the past several centuries if not also millennia of semischolarly and at times exhaustive history of handknotted rug and carpet making before finally broaching the subject of contemporary – hereafter defined as it is within the book as any rug or carpet made since the end of the nineteenth century – somewhere between a third to half of the way through the book. By the time that happens one will know all about Z and S twists in yarns, the difference between an assortment of flatweave types, knotting techniques, obscure and extinct weaving traditions and groups, and other information deemed relatively useless outside of the ultra-niche circles in which I and other rug snobs revel.

Moreover, while the book contains plentiful quantities of useful and factual information, these data are regularly overshadowed and sullied by an outmoded mindset and worldview reflective, one not only presumes of the octogenarian authors, but that the authors themselves take responsibility for on the copyright page of the book2.

For those with only a cursory interest in rugs and carpets this may be offputting, yet for those who are ‘carpet collectors, lovers, consultants, consumers and all who are interested in the artform2’ which the authors overtly state as their target audience, the book provides a wealth of genuinely interesting and useful information. Discerning what of that information is factually accurate, which is conjecture, and which is just plain incorrect is an unfortunate problem which will not only plague serious readers with a critical mind but also confuse, misdirect, and mislead newcomers to the world of rugs and carpets.

For example, on page seventy-six (76) under the section heading ‘Gender Diversity in Carpet Production’ is a particularly offensive and misogynistic statement, directly quoted herein: ‘It [weaving and knotting] requires a high level of attention and skill and is mainly done by women, because their hands are better for this work than those of men.’ Upon reading this passage I was forced by my temporally contemporary and modern sensibilities to stop reading; I only resumed a few weeks later after debating the course of action to follow.

On one hand I was aghast at such a statement for it patently ignores literal millennia of societal mistreatment of women as somehow inferior, just as it likewise skirts dangerously close to tacitly perpetuating other false narratives such as ‘tiny hands make tiny knots’ which at times has been used in false justification of child labour, and also that of primary source eugenics literature from around the time the authors were born. Of peculiar note is that elsewhere in the volumn the authors accurately describe how in some countries – India for example – handknotting of all degrees of fineness is done primarily by men without explaining this discrepancy. Almost as if the aforementioned misogynistic statement was factually inaccurate, which I assert is the case.

Perhaps the authors ignore this discrepancy due to their disdain for rugs and carpets made in India. On page 113 they assert that ‘In this country [India] you can make everything, so long as originality is not an issue,’ and on page 186 they likewise falsely claim that ‘Indian ‘Tibetans’ lack most of the handmade charm of the Nepalese products.’ Sigh… . While this writer has a widely known love of Nepali made rugs and carpets, I still examine each piece individually because every contemporary rug producing country makes a wide range of qualities with hugely disparate levels of finesse and one could argue interest or merit – whatever that means. It is not a carte blanche comparison between countries and to perpetuate this erroneous conclusion is to do a great injustice to any weaver, in any country, who creates world class carpets which resonate with consumers, collectors, and intelligentsia.

I want to ignore this as a generational problem I and many of you can and will outlive, yet doing so would require giving not only the authors but the editors, distributors, printers, and the like a free pass for spreading these falsehoods; the wisdom one should divine from all this information seemingly unfound. In the contemporary era, particularly the woke period of the early twenty-first century this simply cannot stand and those who allowed this statement to enter print should reflect upon their tacit endorsement of this drivel before again contributing to the printed word, inviolable as it is perceived to be.

Statements such as ‘…a perfectly preserved used carpet is highly valued, because time and exposure to light give a better appearance and greater charm.’ as found on page 145 of ‘The handmade Carpet’ tend to ignore the subjective nature of aesthetics and attraction.

Michael Christie, The Ruggist

Interspersed throughout the book are other examples of statements which at times either are or border on being misogynistic, xenophobic, colonial, or otherwise. They are not enumerated extensively herein but for example in the same section of the book wherein the authors deride Indian carpets, they misidentify the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal as the Kingdom of Nepal even though the republic was declared over a decade ago in 2008 CE. These are the discrepancies and inaccuracies which cause one to question the veracity of the entire volumn and those interested should take notice that to read ‘The Handmade Carpet’ is to experience the world of rugs and carpets from the perspective of authors born during World War II. If only there was a colloquial equivalent of ‘Okay Boomer!’ which could be said to the Silent Generation.

All of the preceding notwithstanding, I simultaneously remain drawn to and captivated by the book. Fantastically insightful commentary such as a seemingly genuine consideration that weavers should be paid more (Hear, Hear!), the viewpoint that commercialization damages a cultural product (Hey Morocco, guess what’s going to happen to you!), and that poverty generally forces people into weaving (Is it really a cherished profession?) betray the authors’ genuinely thorough understanding of the subject at hand, even if their perspective, like my own, is heavily distorted by their experience and various -isms, -ogenies, and -ics. Pun intended.

An example of praiseworthy is Section One, Chapter Four, pages forty-nine to fifty-four (49-54), ‘Why Become a Carpet Collector’ which may well be the best reasoned argument for collecting I have ever read and furthermore offers superior advice for those serious about forming a proper collection and not just gathering objects: Find a theme that resonates with you. Hmmmm… . For my burgeoning collection this means novelty and whimsy. Seriously, could it be anything other?

Langauer and Swietly’s experience within the carpet trade then beautifully informs the second half of the work which is worth every minute spent reading. Part Four, ‘Buying, Selling, and Keeping’ (pages 235-289) is a tour de force history of contemporary rug trading and making told from the perspective of European rug traders. Paired with Part Three, ‘A World of Carpets’ (pages 141-234) which highlights each of the major rug weaving regions of the world, and the reader comes away with a fantastic and informative history of the commercial rug and carpet trade as well as carpetry itself. Any current trader, designer, maker or otherwise of carpets who endeavours for success would be wise to read and thoroughly study both of these sections for they hint at the future fate of the handknotted rug trade.

To summarize. In retelling the accounts of numerous formerly prosperous and often no longer extant firms specializing in the import and wholesale of rugs from both the Orient and the Far East a theme is apparent. Time and time again, due to factors both within and outside of the control of these alluded to firms, there is an inevitable outcome: failure. Factoring in the now pervasive transformative information technologies of this era and it seems to this critic that Langauer and Swietly have missed a non-pastiche and glistening golden opportunity to transform all the knowledge and information – good, bad, or otherwise – in ‘The Handmade Carpet’ into wisdom useful to guide carpetry further into the twenty-first century and beyond.

In its stead the reader is left with summaries which seem more like self-serving endorsements of the authors’ own business interests than conclusions based on the information presented in the book and the realities of this era. Exempli gratia: In the ‘Sales Strategies’ chapter, pages 259-264, of Part Four, ‘Buying, Selling, and Keeping,’ the authors lavish praise and support for ‘wholesale carpet trade services2’ further stating these services are to continue to be of major importance. While I will concur insofar as it applies to inexpensive wares of no considerable authenticity or merit, – the antithesis of those described within the book – for the rugs and carpets clearly favoured by the authors, I postulate new emergent distributions models are to supplant the former. And how can they (k)not? If the model has always eventually failed in the past, methinks it reasonable to conclude it is time for a new, dare one say, sustainable approach.

In an age when transportation companies own no vehicles (UBER), lodging companies own no property (AirBNB), and all information and opinion is treated by the vox populi as somehow equal (Social Media), one must accept or at least acquiesce to the reality that disruption has always haunted the rug and carpet trade and that in this era is – I theorize – about to transform the industry in ways hitherto unseen.

Amongst the numerous examples of companies who have come and gone the authors state that various concerns have at times wanted to change production locales to ones ‘where no high management costs were incurred.2’ It is disappointing then that Langauer and Swietly do not apply similar logic here to consider that in 2020 CE perhaps those management costs, which include advertising and marketing of flashy Western Brands of rugs and carpets – which I myself love and delight in – and even the very ‘wholesale carpet trade services’ endorsed therein, might be imperilling the industry, such that it is.

In affixing word to page, the authors present ample information and knowledge within ‘The Handmade Carpet,’ and indeed repeat cultural wisdom from the societies wherein carpetry has long been practiced if not also exalted and celebrated. On first read, ‘Carpet owners assume the moral obligation to keep them in good condition2,’ may seem a bit onerous, authoritative, demanding of respect, and hint at snobbery, yet I think this not the case. It derives from cultures who place value on human labour and the fruits thereof and while originating from a time when dirt was new, now seems appropriate critique against the disposable consumerism so rampant since the last fin de siècle. ‘The Handmade Carpet’ dutifully examines and explains the sum of culture embodied in a handknotted carpet and argues for their preservation and respectable treatment. On the eve of great disruption brought about by myriad factors, this statement is the most prescient; we must value what we have before it is lost.

For this writer ‘The Handmade Carpet’ is an excellent resource filled with observations that span great fluctuations and transformations in the rug market. It adds perspective and insight, and fills in some gaps which can perhaps only be told by those with first hand experience. At the same time, it repeats conjecturous stories as fact, and relies on acknowledged but uncredited others to supply text in many sections. As much as I agree with so much of what the authors have written, I have difficulty ignoring the tarnishing nature of the more insensitive and out-of-touch remarks contained in the book. As supplement and complement to an existing library ‘The Handmade Carpet’ remains a must have and read, but if one were to read only one book on the topic of handmade carpets, – particularly as a newcomer to the genre – I strongly suggest other works to be better suited; said another way, it should not be solely that of ‘The Handmade Carpet.’

[Editor’s Note: The post was edited on 31 December 2019 to polish the language of a few sentences. The overall tone of the review was not changed.]

Disclosure: The assertive authors, via the packager and distributor of the book, Hali Publications, Ltd. of London, United Kingdom provided The Ruggist a complimentary copy of the book for review, requesting in part that said review be published on The Ruggist. After thorough reading and reflection upon the contents thereof, this is that review.

- 1.Definition of Contemporary. Merriam Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/contemporary. Published December 2019. Accessed December 30, 2019.

- 2.Langauer F, Swietly EA. The Handmade Carpet: A Comprehensive Guide to Contemporary Handmade Rugs. London, United Kingdom: Hali Publications, Ltd.; 2018.