Within the world of rugs and carpets if one is to mention ‘Tiger Rug’ the foremost thought ought to be that of Tibetan Tiger Rugs. Not because of any exclusive domain over the motif – which there most certainly is not, but rather because in the grand and storied history of tigers as inspiration for carpets Tibet has produced some of the most amazing, lively, and original versions of the design. Whether the motif originated in Tibet, in a geographically proximal region, or in Timbuktu as a metaphor for far-off unknown places, is a scholarly debate for another time. Regardless, know that amongst the collectable and pre-commercialized rug market, Tibetan Tiger Rugs are, if you’ll pardon the pun, the cat’s meow.

Of course, we now live in the post-commercialization era and as such virtually all, no literally all, rules, suppositions, and assumptions regarding the fixing of a particular design to a certain region are to be disregarded. Rug and carpet designers can and do make whatever design seems to suit the whims of fashion in whatever region also meets such fickle demands. Thusly, this discussion shall not focus on the minutiae of antique Tibetan Tiger Rugs, but rather reference them as a highly influential benchmark and inspiration for the relatively recent and contemporaneous production of Decorative Tiger Rugs.

As several tellings of the history of antique Tibetan Tiger Rugs go, the very first documented arrival of such a glorious rug in the west supposedly occurred in 1979 when one was purchased by and made its way to the Newark Museum in Newark, New Jersey. Though this date is oft repeated across many websites describing Tibetan Tiger Rugs utilizing virtually identical text it, on closer examination, appears to be incorrect. The correct date, according to the date of acquisition of the Newark Museum’s first Tibetan Tiger Rug, is 1976. I mention this seemingly innocuous inaccuracy as it perfectly illustrates our human fallibilities when examining events and items within our own lifetime, let alone that of centuries past. It should serve as a reminder that in absence of irrefutable proof, much of what we discuss regarding rugs and carpets – either academically or merely decoratively – is subject to the Sixth Opinion.

To the Trade: When speaking of antique rugs and carpets much consideration is paid to both the origin and to the design, as those two (2) elements are often inextricably linked. As trade, and thus influence, spread around the world these two (2) components became less strictly tied together reaching the point today where – in new production – it is the exception rather than the rule. A design can be inspired by anything the world over, and often times the carpet is made where it makes most economic sense. Always ask about both the design and origin of the carpet.

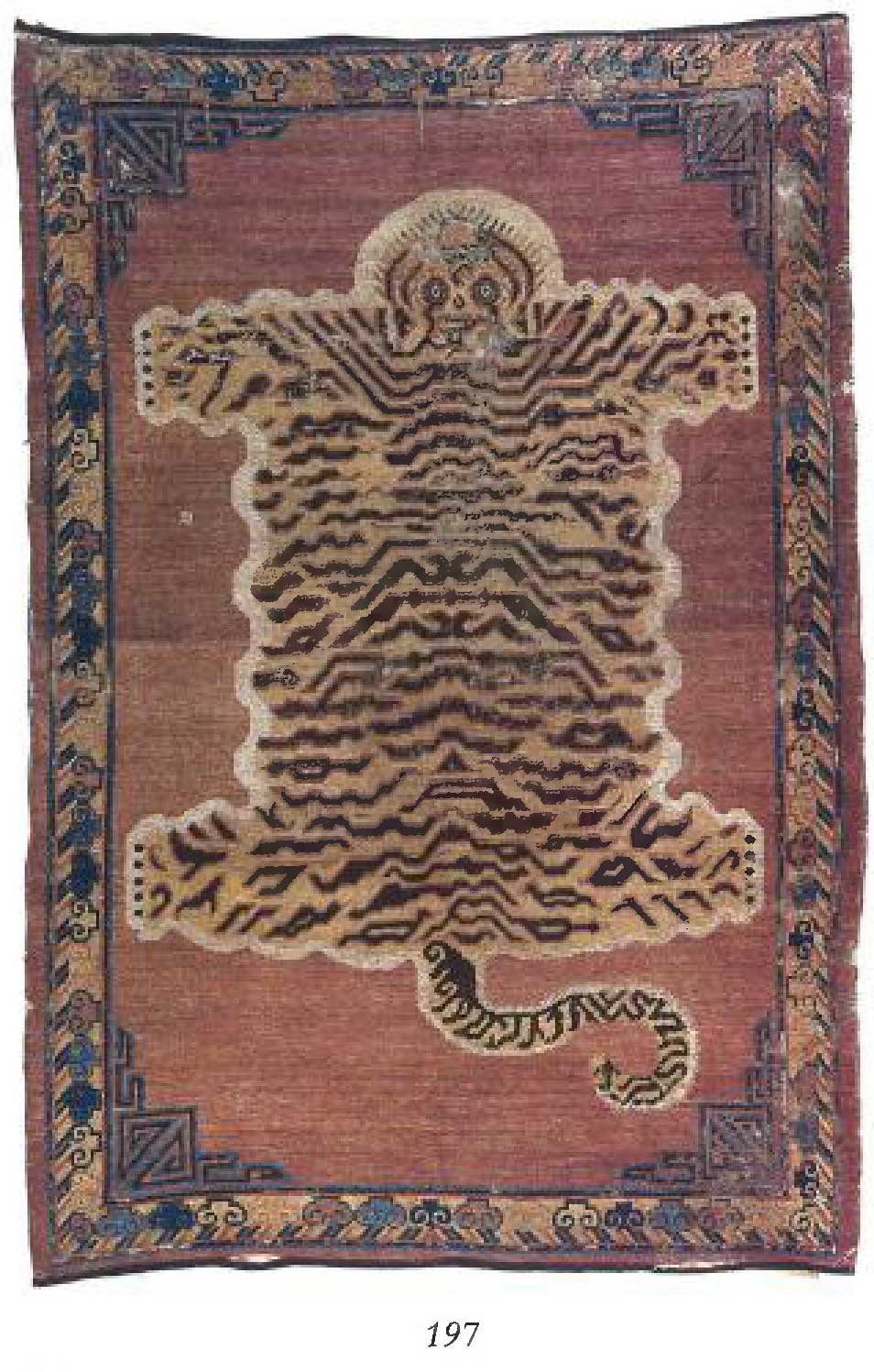

That lengthly prelude now complete, the discussion of modern production Tiger Rugs will begin where it must, with a brief primer courtesy of the Newark Museum who graciously located the above image and the date of the acquisition. From the museum: ”Flayed Tiger Skin Rugs’ were used by Tibetan lamas as sitting rugs, representing the Buddhist taming of the wild ego-centered mind. These probably replaced actual tigerskins used earlier in Tibet. This [in reference to the rug above] bold cartoon-like rug has the deep wool pile and bright colour of traditional Tibetan weaving.’

As the decade following the arrival of said rug waned a seminal work on the subject at hand was published in 1988 entitled ‘The Tiger Rugs of Tibet’. Edited by Mimi Lipton with contributions from a variety of experts in the field of rugs and carpets, the book is a wonderfully illustrated tome which attempts to decode the enigmatic history of the Tibetan Tiger Rug. From the book’s excerpt: ‘Tibetan tiger rugs were owned solely by the elite, who used them both to sit on and to cover their luggage on long journeys. They are very rare, there are probably fewer than 200 [antique carpets] in existence, their history and usage still shrouded in mystery. Yet the diversity, creativity and apparent modernity of their designs are astonishing: their beauty a source of wonder and inspiration.’

Tibetan Tiger Rugs of the antique and old variety can generally be classed into one of three distinct groups, though for pedantic reasons already mentioned, there are those scholars who further sub-categorize the designs; something I feel is a bit overzealous. The first general group then is that of what I consider the archetypal tiger rug: The ‘flayed’ style which – as the name indicates – depicts a pelt complete with arms, head, and claws attached. Second, is the ‘abstract’ style which portrays the stripe of the tiger in a more representative and conceptual manner and is the style to which ‘apparent modernity of their designs’ is in reference. The third is ‘paired’ which illustrates tigers walking in pairs; an apparent and direct result of Chinese influence representing Yin and Yang. Further sub-categories, if they are to be used, generally only add descriptors to these main categories, such as ‘realistic pelts’, ‘double headed’, ‘wavy stripes’, et alia.

The late nineteen eighties also corresponded with the beginning of the modern rug and carpet revolution and the continued commercialization of decorative carpet weaving, which to be frank, owes much of its existence to the immediately aforementioned astonishing beauty as a source of inspiration. During this period much of the work being introduced to the west was based – sometimes literally and to be frank occasionally bordering on what would now be considered a potentially copyright infringing manner – on very classic designs, particularly the flayed and abstract varieties. ‘Those were the days.’ begins Tom DeMarco, Owner of Kooches and General Manager of Odegard, ‘Was it the summer Atlanta show in 1989 or the winter show of 1990 when at Tufenkian we first showed our far reaching, fun, colourful collection of tigers? It had to be not too long after ‘The Tiger Rugs of Tibet’ was published and my hat is of to Mimi [Lipton]; that book spawned a fairly strong cottage industry.’

‘Kitty Play Ball’ as shown above is one such example of a quintessential Tufenkian interpretation of the flayed aesthetic and as James Tufenkian, founder of the eponymous house states: ‘[is] a design that features rainbow motifs at each end and the tiger embracing the jewel of wisdom. To create a design with a bit more whimsy, we removed some traditional iconography from the rug and chose a colour palette that would de-emphasize the tiger’s fangs and claws.’ Though the look of this carpet may now in 2016 appear dated to many, in the early nineties it was exotic, and for westerners who were far more accustomed to the classic Persian stylings which had long dominated the market, these tigers were fresh and fun. Tom adds: ‘I thought they were great and they added some levity to the offerings at a time when it was readily accepted [by consumers]. Business was good in the Tibetan/Nepalese rug industry and we had a roster of solid, talented, successful dealers willing to make a market with us.’

Dealers like the now retired Patrick Aaron of floordesign in San Francisco and the ‘late great’ Jackie Vance of Jacqueline Vance Oriental Rugs in New Orleans were two (2) such dealers making a name not only for themselves, but for Tufenkian and indeed tiger rugs. ‘When Patrick Aaron or Jackie Vance – two of the most generous rug dealers I have ever known – told every dealer they were acquainted with that the Tufenkian Tiger rugs are great, people listened. The Tigers sold through and the dealers kept selecting them for years.’ Tom says of Tufenkian sales at the time.

Just as the antique tiger rugs inspired Tufenkian so too did they inspire another westerner then at the vanguard of rug and carpet design: Stephanie Odegard. Mr. DeMarco again, ‘When I arrived at Odegard in 1993 I discovered that Stephanie Odegard had embraced the Tiger rugs from Mimi Lipton’s book as well, but the more abstract versions.’

[wc_row][wc_column size=”one-half” position=”first”]

[/wc_column][wc_column size=”one-half” position=”last”]

[/wc_column][/wc_row]

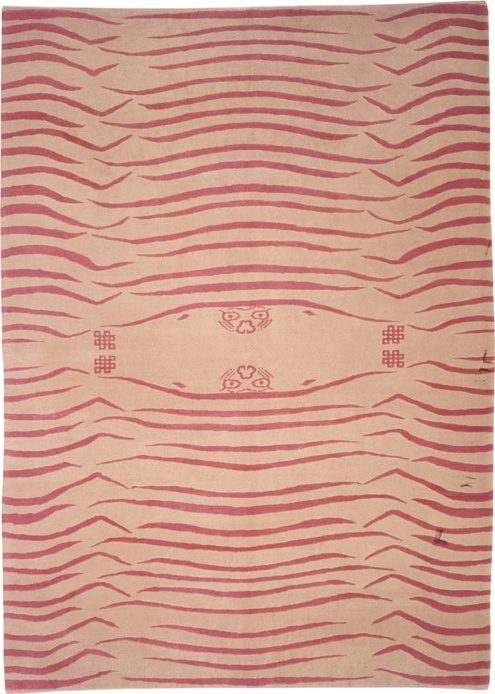

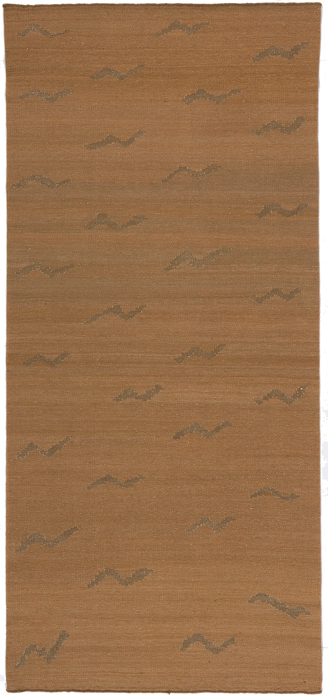

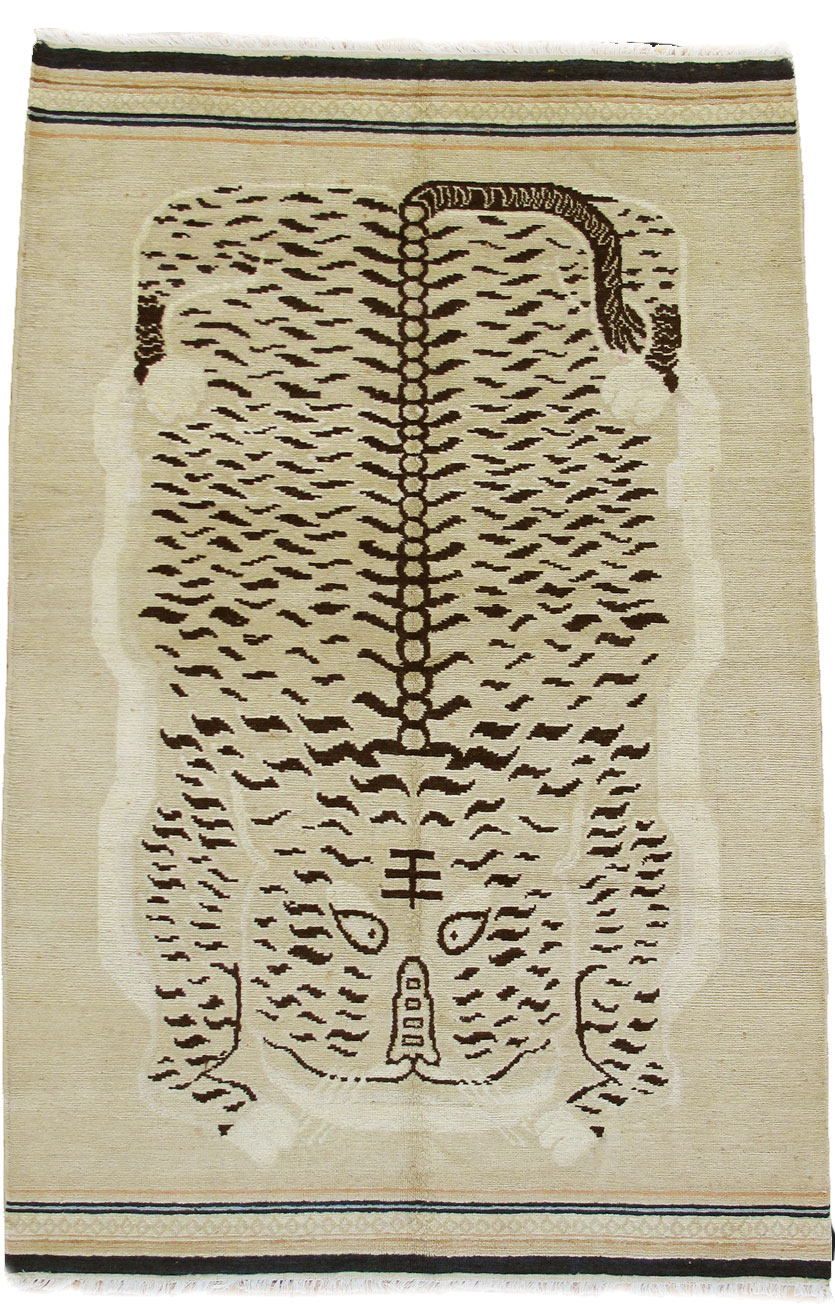

‘Takri 6’ by Odegard as shown above is an embodiment of abstraction with the notion of modernity heretofore described. Moreover, if one were to be pedantic the carpet could be further described along the lines of an ‘abstract double-flayed tiger carpet’, with the heads readily apparent and endless-knot motifs charmingly taking the place of the opposing front paws. To further the abstraction the design is reduced to a two colour palette well suited to the needs of the decorative market, eschewing a strictly artistic interpretation. In ‘Takri’ by Kooches, Tom DeMarco further attempts to abstract the tiger’s unchangeable stripes with an exceptionally minimal design whose origins could be all but unknown when examined in absentia of context.

We reference this early work of Tufenkian and Odegard, plus the later work of Kooches to both draw the direct comparison to antique Tibetan Tiger Rugs styles and say this is what the first iteration of western influenced adaptation looked like: Highly recognizable as derivative of traditional Tibetan motifs and imagery.

And then, like all fashion cycles, you couldn’t sell a Tiger rug at BOGO (Buy One Get One (customarily free)), a GOB (Going Out of Business (often repeatedly)) sale, or by donation. And then (again), here it is 2016 and ‘I have seen a number of differing and artful versions of the tiger [rug] from different manufacturers popping up over the past year. I find many of them very artful and dare I say, beautiful.’ begins Ryan Higgins of Tamarian. This is not to say tiger (or by extension any animal design) has ever gone out of style, but there are certainly peaks and valleys. ‘We produced a design ‘Tigris’ and still have several in stock, especially in the famed ‘Mocha Blue’ colorway (If you recall Mocha Blue was Beige’s sexy cousin [Author’s note: Ryan is teasing me about my disdain for beige]). It was a decent seller about ten years ago, but a very small part of our market.’

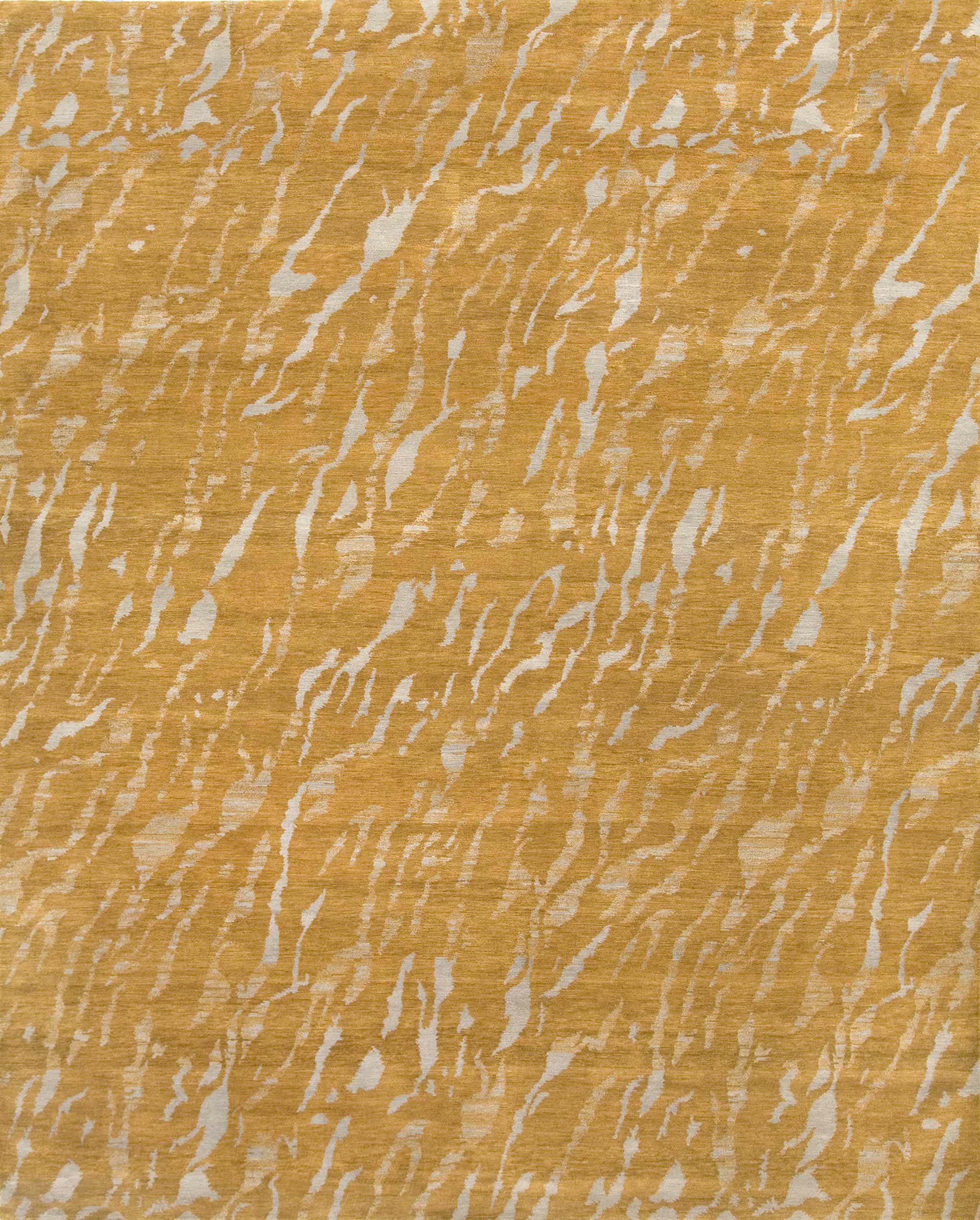

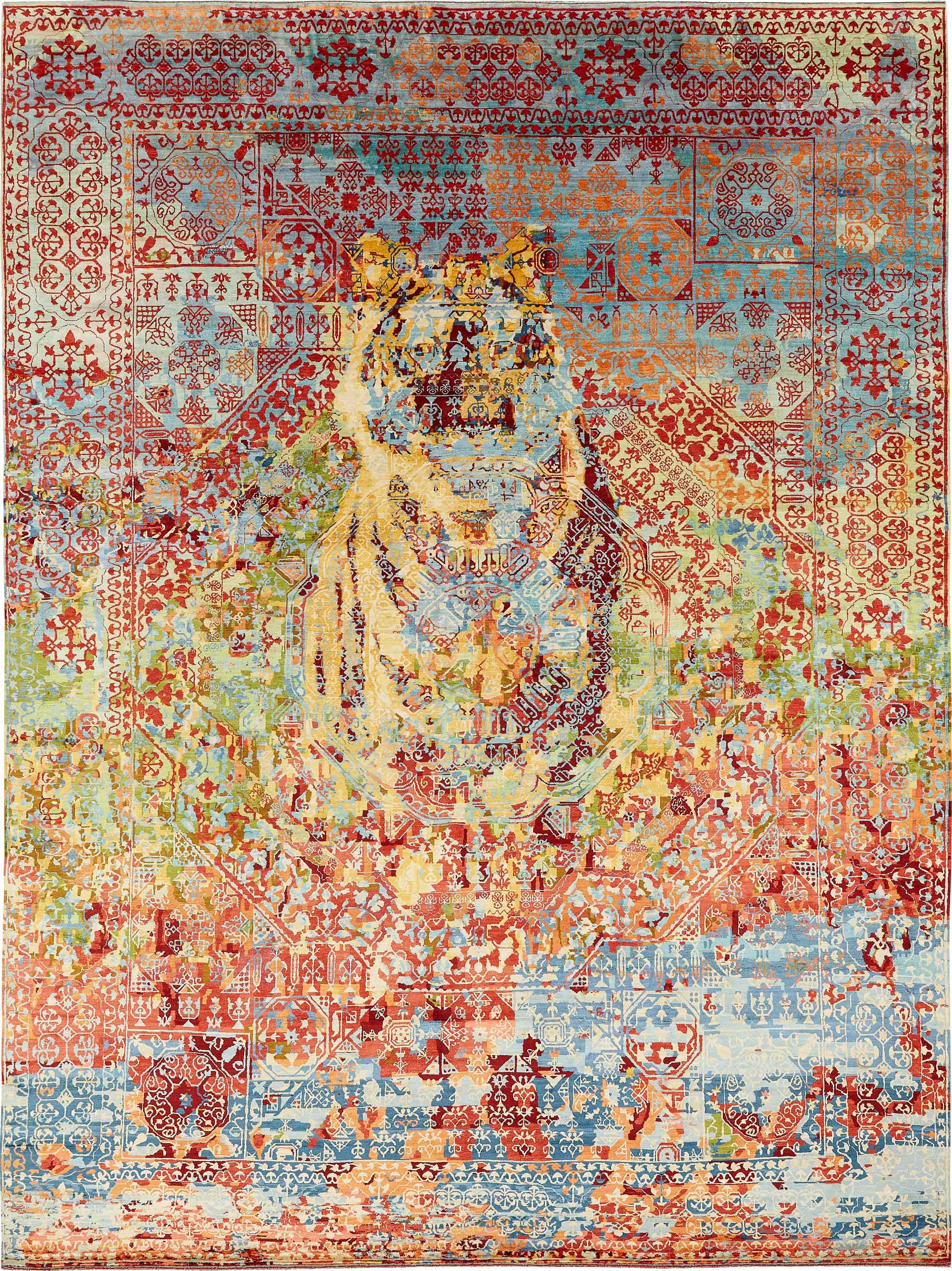

‘Tigris’, as shown above, from Tamarian is a superb example of what I would call second iteration adaptation. The change in styling directly reflects western influences and decorative demands on the design and colouration. Its all-over patterning is very friendly toward furniture placement, the colour – while customizable – is presented in a very accessible palette, and it is a good looking agreeable to most carpet. For purists like myself, it has not the charismatic ‘wow’ of other Tiger Rugs, but then again the vast majority of consumers are not purists, and therein lies the broad appeal.

No discussion of purists (in the rug industry) would be complete without inclusion of the work of Joseph Carini, of the eponymous Joseph Carini Carpets, and I say that with the utmost regard for the supreme caliber of his work. In his modernistic approach to creating carpets produced to not only be artistic/decorative but as directly influenced by the leitmotif of Tibetan Tiger Rugs as possible, we see a certain spirituality about the design. Joseph begins: ‘My interest in tigers started early on when I began to learn about Tibetan Tigers. The tiger rugs intrigued me and I had the opportunity to work with a vast private collection around the 1990s. I was also intrigued how the tiger was a power animal in both Buddhist and Hindu religion. Many icons have been depicted sitting on tiger rugs. The essence of the animal was always intriguing, perhaps it has something to do with subduing passions, so perhaps a holy man sitting on a tiger represents subduing passions.’

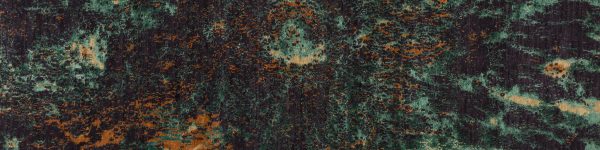

And what passion one must subdue whilst sitting yourself or your furnishings on ‘Tiger’ from Joseph Carini. Clearly the design – disregarding colour – is an interpretation of a flayed tiger pelt, however, by presenting a cropped view of the pelt at an aggrandized scale the carpet becomes more abstract thus less intimidating decoratively than it otherwise might be. As for colour, Joseph explains again: ‘I wanted to make a tiger carpet that is unique, and not another copy, but instead something that’s never been made. I wanted to make a tiger rug that was just as good as the Tibetan Tiger [Rugs], coloured in a different way, with more of an artistic influence. Instead of designing the tiger to be literal I wanted to focus on it being artistic. Although today it’s a fairly esoteric design, to be used in a house it’s always classic and never goes out of style.’

Just as the carpets of Joseph Carini belong to my now arbitrarily defined third iteration interpretation – based on the thematic – so too do the carpets of New Moon embrace the notion of the tiger, though with strikingly different aestehtics. ‘One of the things that’s interesting about the history of Tibetan rug weaving is the Chinese history and influence. Animal motifs in general and specifically tigers have historically been incorporated in artwork taking influence from Chinese culture. One would often see tiger pelts pictured in Chinese art, a symbol of dominance and luxury. The origin of rug making then took its influence in the early stages from these pelts used as floor coverings.’ says Erika Kurtz, second-generation president of the family run New Moon, a carpet house that like Tufenkian and Odegard was also there at the outset of the decorative market. ‘There was an emulation of animals skins in the first floor coverings. The evolution has now come full circle with a more stylized use of animal imagery in general with traditionally shaped [rectangular] rugs. Our ‘Khan’ rug takes inspiration from traditional Tibetan Thanka art which has also been influenced by the Chinese culture and iconography. The traditional pelt re-imagined.’

To the Trade: Perhaps at this point it is worth mentioning that due to the length of the discussion regarding the geopolitical circumstances of Tibet and China we have intentionally forgone mention of it to this point. In short, distinct Tibetan culture has, is, and likely will continue to be threatened by Chinese culture. Many Tibetans fled Tibet proper to Nepal after the Chinese occupied Tibet and took with them their artistry. Up to this point the discussion has focused on the Decorative Tiger Rugs made in Nepal as they are the most direct successors to antique and old Tibetan Tiger Rugs. As Mr. DeMarco so succinctly stated with ‘Tibetan/Nepalese rug making’ it should be noted the overwhelmingly vast majority of today’s – meaning from the late eighties onward – traditional Tibetan style rug weaving is made in Nepal and the two terms are unfortunately often conflated.

[wc_row][wc_column size=”one-half” position=”first”]

[/wc_column][wc_column size=”one-half” position=”last”]

[/wc_column][/wc_row]

That notwithstanding, the changes begun in the late eighties with the start of the modern carpet revolution continue to this day. The cycles of multi-cultural influence continue ever faster, and Tiger Rugs – in their various forms – continue to further evolve. As briefly mentioned earlier we had intentionally left open the debate on the origins of the tiger motif so as to spur conversation and thought regarding what importance that fact, if any, plays in today’s decorative and commercial driven rug market.

As noted in the description of the above 19th century Khotan Tiger Rug from the Christie’s 14 February 1996 catalog of ‘The Bernheimer Family Collection of Carpets’ sale: ‘Although well documented in Chinese and Tibetan rugs, the tiger pelt design is unusual for carpets from East Turkestan.’ So while Tibet and China may have long held a hegemony over the tiger motif, even one hundred years ago the design was being emulated, copied, or perhaps even just naturally inspired in the diaspora.

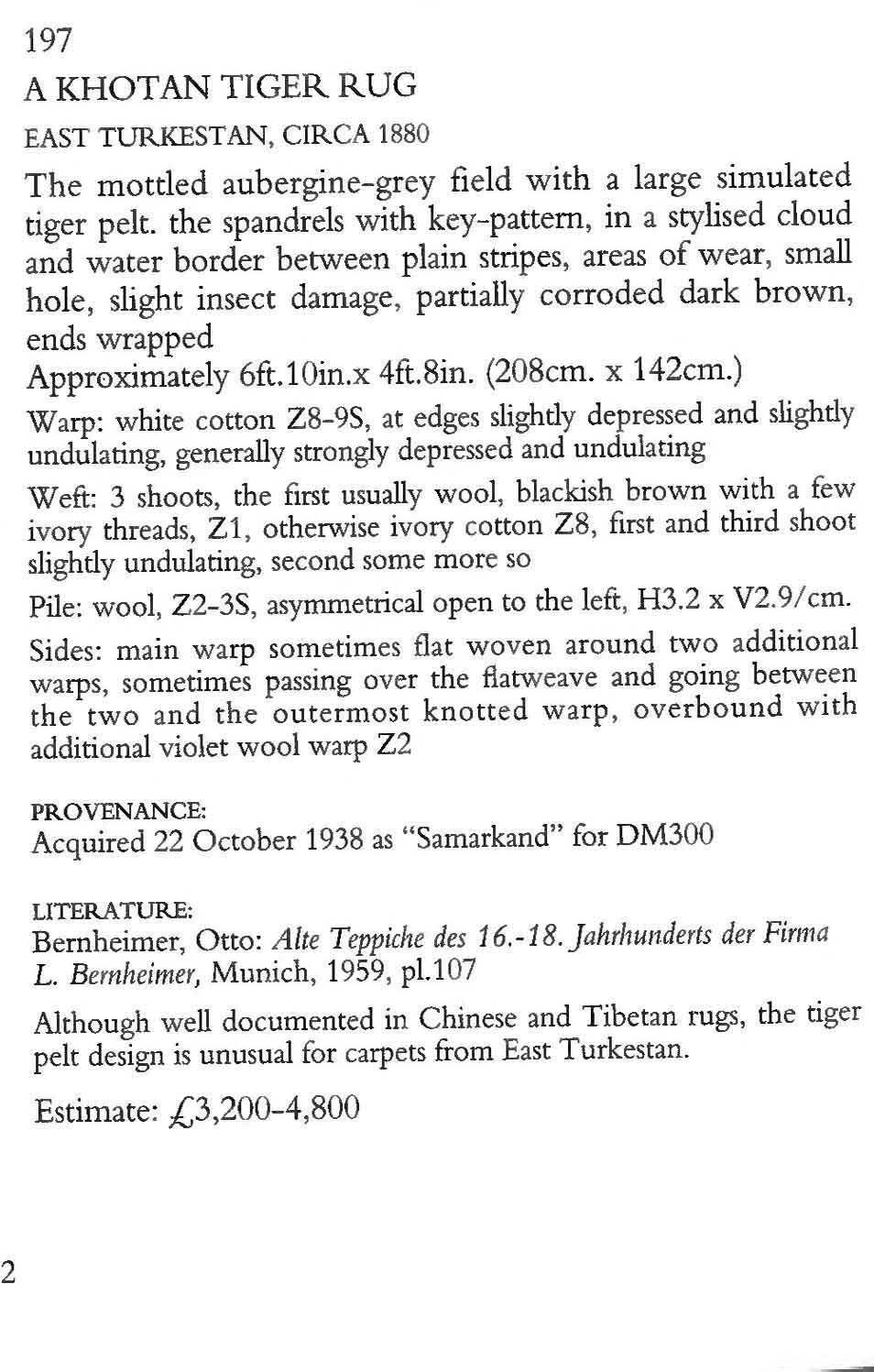

With that comes a starkly different and entirely contemporaneous interpretation of the tiger which eschews the confines of past in favour of something wholly modern; the ‘global’ iteration if you will. From Wool and Silk: ‘Part of our Wildlife Collection, ‘Tiger’ is a finely woven, 100% silk creation, handknotted in India. Inspired by his love of wildlife and adventure, this rug was designed by Erbil Tezcan’s son, Anka. Anka took an image of a tiger and transposed it into a traditional Mamluk design. The subtle image of the Tiger leaping out of the medallion is symbolic of rebirth and the freedom we feel when we are one with nature.’

What makes this Tiger remarkable is that it represents perhaps the ultimate (so far) evolution in the Tiger motif. By combining not only iconography, design, materials, and workmanship from geographically disparate regions, but also abstract colouration and an artistic statement, with the modern computerized design technology that makes such work possible, this Tiger unifies all of the previously considered thoughts into one statement: Beauty knows no boundaries. ‘Tiger’ from Wool and Silk represents the globalized state of design in 2016 just as ‘Kitty Play Ball’ and ‘Takri 6’ represent their time’s slightly less worldly and exotic nature.

[wc_row][wc_column size=”one-half” position=”first”]

[/wc_column][wc_column size=”one-half” position=”last”]

[/wc_column][/wc_row]

While beauty may be boundless, it is of course subject to the eye of the beholder, and as Erika Kurtz said of the tiger design, we now, once again, ‘come full circle’ to behold two (2) distinctly beautiful carpets.

‘Gorden Tiger’ by Odegard is the rug that inspired this entire article. It’s a nod to traditional Tibetan Tiger Rugs but with western influence and just that touch of whimsy I find so desirable. Nothing however can match the extreme whimsy of Tufenkian’s ‘Gladys’. As another flayed style rug it takes the concept just that much further by removing the pelt from the confines of a rectangular carpet to fully mimic a true skin while remaining far more ecologically sensitive. Again from Tufenkian: ‘Tiger skins have a rich history in Tibetan iconography. Yogis have been depicted meditating on tiger skin rugs, where the tiger is shown as a protective force that keeps the influences of the outside world away from the yogis in both a spiritual and literal sense. Today, the same thing could be said for rugs like Tiger Gladys Black. As the centrepiece of a room, it can help to protect you from the world and create an oasis of calm in your favourite room.’

Whether or not you find Tiger Rugs appealing is of course a matter of personal taste. Speaking entirely decoratively however there is a remarkable and enduring (read: timeless) appeal to animal prints that routinely and cyclically brings them back into fashion and a Tiger Rug is no exception. Tom DeMarco again: ‘I believe Stephanie [Odegard] embraced the ‘tiger stripe’ rug as a more sophisticated and historical design aesthetic, whereas, James more aligned with the fun, funky accent rug potential of the ‘tiger pelt’ designs. The truth is, tiger rugs can be both.’

The Ruggist wishes to thank Joseph Carini, Tom DeMarco, Ryan Higgins, Erika Kurtz, Erbil Tezcan, and James Tufenkian for their contributions. Special thanks to Elisabeth Parker of Christie’s and to the Curatorial Staff at the Newark Museum.

Wool and Silks’ ‘Tiger’ will debut at The Rug Show 10-13 September 2016 as will new introductions from Tamarian, New Moon, and Tufenkian. Odegard and Kooches will be showing concurrently at The New York International Carpet Show 11-13 September 2016. The work of Joseph Carini can be seen by visiting their showroom in TriBeCa.